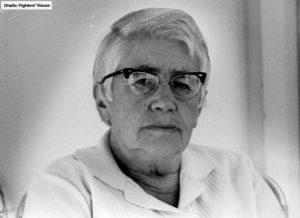

Fruma Gurevitz

When she emigrated to Israel in the 1970s, Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich), a doctor from Kaunas, took with her a lot of material on rescuers of Jews, including their addresses, that she had been collecting for several years. Some time after she settled in Israel, thank-you letters to rescuers of Jews for the lives that they had saved during the Holocaust started making their way to Lithuania. These letters were signed by Gurvičienė herself as well as the writers Icchokas Meras and Mejeris Elinas. The letters from far-away Israel were a genuine surprise, especially since they were written in the times when the topic of rescued Jews was not popular. This gesture of respect brought joy to many rescuers, or to their children and relatives, if they were no longer alive. Antanas Zubrys died in 1951, Matilda Zubrienė in 1970 and it was their children who received the warm letters of the most profound gratitude.

When she emigrated to Israel in the 1970s, Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich), a doctor from Kaunas, took with her a lot of material on rescuers of Jews, including their addresses, that she had been collecting for several years. Some time after she settled in Israel, thank-you letters to rescuers of Jews for the lives that they had saved during the Holocaust started making their way to Lithuania. These letters were signed by Gurvičienė herself as well as the writers Icchokas Meras and Mejeris Elinas. The letters from far-away Israel were a genuine surprise, especially since they were written in the times when the topic of rescued Jews was not popular. This gesture of respect brought joy to many rescuers, or to their children and relatives, if they were no longer alive. Antanas Zubrys died in 1951, Matilda Zubrienė in 1970 and it was their children who received the warm letters of the most profound gratitude.

In her article “Spring of 1944” (“1944 metų pavasaris”) in Soldiers Without Guns (“Ir be ginklo kariai”), edited by Sofija Binkienė (Vilnius: published by Mintis, 1967), Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich) lays bare the despair of the people behind the barbed wire of the Kovno Ghetto when, after the “children’s Aktion” in the Šiauliai (Shavl) Ghetto on November 5th, 1943, they realized that mortal danger looming, it seemed, inevitable, over all Jewish children. Sadly, only a minority of people imprisoned in the Kovno Ghetto managed to find acquaintances from before the war who would take in and hide their children.

Having survived the horrible “Children’s Aktion” in the Kovno Ghetto on March 27th and 28th, 1944, Frúme Gurvich decided to look for shelter for her five-year-old niece Naomi as well as her daughters, twelve-year-old Etta and sixteen-year-old Bella. She wandered through her home city of Kaunas, now hostile and alien, and first of all contacted her former colleagues, Kaunas doctors. Sadly, some did not have enough courage to even look her in the eye. Some slammed their doors in her face. Fruma almost succumbed to the terrible despair. But then, a miracle happened.

In her memoirs, Dr. Fruma Gurevičienė (Frúme Gurvich) wrote:

To the end of my days, I will not forget the way I was taken in by Dr. Matilda Zubrienė and her husband Antanas Zubrys. How they calmed me down and even gently scolded me, parent-like, for not coming to them straight away. I could not believe my ears. They agreed to take in one of my daughters and disguise her as a shepherdess in the countryside. I warned them, once more, that my daughters were brunettes and that they were easily recognizable. To which they answered: “Is it their fault that their hair is black?” How delighted I was to hear such warm words. How much hope and trust in humankind they brought me.

Since Antanas and Matilda Zubrys’ house stood on Donelaičio Street in the center of Kaunas, they decided to take Gurvičienė’s daughter Etta to a safer spot: their own farm in Armališkės. There, Antanas Zubrys had already been hiding Haris Goldbergas, son of a Kaunas lawyer, for a period. Those wartime days in Armališkės with Eta Gurvičiūtė and Haris Goldbergas are well remembered by Aldona Bogdanienė, daughter of Antanas and Matilda Zubrys, who is still with us today.

Dr. Fruma Gurvičienė’s risky wanderings through Nazi-occupied Kaunas in search of rescuers for her girls had a happy ending. Her little niece Naomi was with no hesitation accepted by her former course mate, Dr. Marija Butkevičienė: together with her own daughter Ona, and and her son Povilas. They cared for the little girl for some six months, up to the autumn of 1944. And, the elder daughter Bella was rescued by Dr. Ona Landsbergienė, the chief doctor at the Department of Ophthalmology at Kaunas Clinic. After having carefully listened to Fruma’s plea, she gave a laconic answer: “Let her come.” From the Landsbergis’ family home in Kaunas, Bella was moved to their summer house in Kačerginė, where she was cared for by all members of the family.

From: Defending History

Dr. Fruma Gurevich from the Vilijampole Ghetto in Kovno, describes how she found a hiding place for her three daughters with the families of doctors with whom she had studied, and how she helped other children flee the ghetto.

At long last, I managed to join the women’s brigade, which was taken to work in the city every morning. At dawn, I marched together with hundreds of women, along the uneven streets of the ghetto in Vilijampole. Armed soldiers watched over us, with their rifles at the ready. We passed through the gate, into the streets of Kovno.

The city appears silent, still sleeping peacefully. Lithuanian children asleep in comfortable, warm apartments, those same children who I used to treat until a short time ago, sitting next to them, more often than not, managing to save their lives. And then, at the beginning of the war, some of their parents, fathers, indiscriminately axed entire Jewish families to death in cold blood – the old, women and babies. And just here, right in this alley, a pile of corpses with shattered skulls were collected, and over there, on the corner lived my sister, Emma, who is also a pediatrician. She has been sent somewhere. Where is she now? I stand with thoughts running through my mind … but the women in the brigade urge me to go on, so I do. Miraculously, I manage to slip away at an intersection of two streets without the guard noticing. Once behind a courtyard gate, I tear off the yellow patches. Who knows how, later on, when I fall back in line with the brigade, will I manage to re-attach them so that the sentries won’t notice that they are not properly on? With my heart beating one to the dozen, I wander through the streets of this hostile city. I was actually born here, as were my father and grandfather. I had really loved Kovno! How proud I was of it! Who could have foreseen that murderous villains would be living amongst us!

Walking, one step at a time, it feels as if the ground is on fire beneath my feet…I will soon be arrested… I end up standing in front of the small plaque of a doctor whom I know well. The waiting room is full. I don’t want to be with other patients waiting for their appointment, staring at each other with a questioning look in their eyes. I continue wandering. I find the apartment of a different doctor. He isn’t at home. I go to a third one, then a fourth – I was stopped from even getting past the front door, because I had, apparently, been recognized, and the door was slammed in my face. I was losing hope. Despondent, I give it another try – and walk towards the ‘Green Mountain’ to Dr. Marija Butkevičienė with whom I had studied years ago. A small, wooden house. I am sure that I will fare no better here. Wait, what is happening here? I was received with open arms. They sat me down, were sympathetic to what I had to say … (I couldn’t believe my own ears), and agreed to taken in 5-year-old Naomi, our youngest, the first who should be saved.

As soon as I heard them saying that they would take in our little one and I was sure that it would come about, I was filled with indescribable happiness but, at the same time, also anxiety. Why am I imposing such danger on these brave people? I explain to them that the little one has brown hair, and doesn’t look like the rest of the family, etc. But Dr. Butkeviciene, her daughter Ona and her son Povilas try to calm me down and promise that, if we are able to bring the little girl to them, they would do their utmost to hide her.

I left their small, modest house feeling happy and excited, encouraged by their human kindness and generosity. But how was I going to rejoin the brigade in order to return to the ghetto with the rest of the women? But, most importantly, how was I going to get Naomi out of the ghetto? I would sedate smaller children with a Luminol injection so that their parents could smuggle them out in their backpacks when going to work. But Naomi is five, and even if she were very thin, it would be difficult to hide her in a backpack.

Two days later, after much contemplation and planning, we decided to take Naomi into the city in a sack, under a load of potatoes.

We explained to her what we were going to do. Naomi, with tears rolling down her cheeks, said: “I don’t want to leave my mother, but I know that I have to”, and agreed to sit in total silence, without moving, so as not to arouse the suspicion of the German sentry sitting on the cart with his rifle.

The fateful and worrying morning came, dawn was breaking and the sky was still dismal and gray: the little girl is hugging her favorite toy – Mishka, her threadbare teddy bear – and climbs into the sack which is placed on the cart, together with other sacks, and covered with straw for camouflage … and the cart manages to leave via the ghetto gate. Two ghetto workers, who helped to load and unload the cart, sat on top. As usual, they were stopped several times. The German sentry who was also on the cart, was not familiar with the route they were taking. They had agreed to stop at an address we had given them, to take the little girl out of the sack and leave her in the hallway of the house.

Dr. Butkeviciene lives quite a long way from the ghetto so we couldn’t send the cart there. We had to look for a suitable way to overcome this. There was a consultation center for pediatric diseases not far from the ghetto, where one of our friends, who was a medic, worked – a nice young woman called Yelena. I can’t recall her surname. I had previously managed to meet her in the city (which had been very difficult to do), and come to an agreement. As soon as the child reached the center, she was ready to take her to Dr. Butkeviciene. There are usually no strangers around at the Mother and Baby clinics early in the morning and, as far as we could gather, no one saw the little girl crawling out of the sack or being taken to Dr. Butkeviciene. Those of us back in the ghetto had no idea what had happened to Naomi after leaving the ghetto. But the Butkeviciene family must have had much to worry about!

Their apartment was in a low building and there were a number of other buildings sharing the same yard. They had many neighbors including Nazi supporters and others who were simply inquisitive. There was constant danger, not only for little Naomi, but also for this remarkable family.

In the meantime, I was planning to go into the city again. I had to find somewhere to place our two other daughters in order to save them. Once again, I wander through the city’s streets, friendless like a leper, shivering from fear and mental stress. Once again knocking on doors of those who may be able to help. People got scared when they saw me, as if I had risen from the dead. But mainly because my being there gave rise to danger – everyone wanted to be rid of me as quickly as possible.

So much unpleasantness, heartbreak and humiliation! However, the main thing is to save the girls, and so I had to do everything possible so that they don’t fall into the hands of the Gestapo. I shouldn’t have to consider those people’s anxiety, irritability or grumbling when they see me.

There is, in fact, one other way out…

I have, in my possession, tubes containing morphine, strong, fast-acting poison tablets, for me and the girls. But if things get that far, the girls have to be poisoned first. I knew that I didn’t have the strength to kill them myself.

I continue down my own ‘Via Dolorosa’. Once again, I trudge through this hostile city, with the danger of death peeping out of every crevice in its gates. I zig-zag my way along, moving from sidewalk to sidewalk, since each one of the passers-by looks like a sworn enemy just waiting to give me away.

I eventually reach my colleague and acquaintance, Dr. S. She had graduated from university a year after me. She welcomed me but, before I could finish telling her what I wanted, she started complaining about her problems – in spite of all her efforts, she has been unable to find a suitable cleaner.

After hearing what she had to say, I was happy to suggest that my eldest daughter, who was 16, come to clean for her. “That could be a good arrangement”, she said, “but there is no room for a bed in the kitchen, since our large, thoroughbred dog sleeps there, and our landlord is absolutely unwilling to have a dog kennel in the backyard”.

Nu! That’s a good enough reason. These days, dogs are more important than human beings.

I leave her house, broken and shattered, helpless and with no hope.

But Dr. Matilda Zubrienė lives in the same lane near her house. I have already been to her twice, but both times she hadn’t been at home. I will give it another try. This time, I was lucky. I will never forget how Dr. Zubrienė and her husband (who are no longer alive) welcomed me, how they comforted me, calmed me down and even somewhat rebuked me, as my parents used to, as to why I hadn’t come to them before. Once again, I can’t believe my own ears: they are willing to take in one of my daughters and promise to make arrangements for her to be a farm girl in one of the villages. Again, I felt it my duty to warn them that my daughters had brownish hair and it would be easy to discern their origin. Their answer was: “Is it their fault that they have dark hair?”

It was wonderful to hear them say this. What confidence they inspired in me.

Out on the street once more, I saw again the door of the house nearby with a sign showing Dr. S. I compared these two doctors living side by side, but what a difference in their approach.

I hurried back home, to the ghetto. And once again, the worrying thought of how to reach there, how to join my brigade without the sentries noticing. You could write thick books about these complicated and dangerous situations, about adventures bordering on imaginary hallucinations, about the fear and experiences related to escaping from the ghetto and then infiltrating back afterwards – just like adventure stories. However, this isn’t the time or the place. Sometimes, I find it difficult to believe that all this happened to me.

Here we were again, facing the same problem, how to get 12-year-old Etta into the city. We had already spoken to the head of the brigade and decided to get her out of the ghetto as a worker with the women’s brigade. We dressed her in a long coat over her short, child’s coat, wrapped a scarf around her head, and gave her high-heeled shoes to wear. We also gave her a tin of broth and a knapsack made out of an old piece of Gobelin. The women who went into the city to work would take bags like this in which to put shavings that they found there. We put shoes, a school hat and a schoolbag full of books in Etta’s knapsack.

The plan was for Etta to change her clothes in the washroom when she arrived at the place of work, and change her appearance from an adult worker to a schoolgirl. One of our friends, who was in the same brigade, promised to help her and show her the narrow gate which led out to the street.

I described Dr. Zubrienė’s home to Etta and gave her a drawing of that part of the city, and the streets she had to cross. She listened carefully to all my instructions without saying a word or protesting. She was no longer a little girl but like a mature 12-year-old.

Later one, when we were released, Etta confessed that she hadn’t been afraid of the difficulties, the loneliness and the danger of death she had had to face. “It is better to die early on so as not to see my father and mother being killed…”. That thought frightened her more than anything else.

As we had suspected, the sentries didn’t pay any attention to a schoolgirl, and she went into the city easily. And here was a girl of twelve, wandering the unfamiliar streets on her own, looking for the address of good people who she didn’t even know, and who had promised to shelter her. Eventually, she found them, knocked on the door but, when they opened it, she saw that they were embarrassed. It appeared that the timing was all wrong, as they had visitors, and the situation might become dangerous.

Etta couldn’t go into the house at that stage so they took her up to the loft, sat her down in the pantry, gave her food and drink, gave her words of encouragement and came to check on her from time to time. Afterwards, they dressed her in old, torn clothes and told her that she should say that she is a waif from the Soviet Union. Saving Russian children was a lesser crime than saving a Jewish child. With this shabby look, they took her to the village, where she was taken on as a farm girl. She caused no little anxiety, hours of fear and sleepless nights to the Zubrys family who had taken her in, but she wasn’t the only one who worried them. They were hiding many others besides Etta, thereby saving their lives. As little Etta told me later on, those hidden included Russian war prisoners. At dawn, she would see the Zubryses handing out food to people who were being kept hidden in the hayloft, the wheat field or in the garden. Of course, all this had to be kept hidden from inquisitive neighbors, among whom there may be some with a loose tongue, jealous or scheming. However, it would appear that neighbors also treat good people in a friendly fashion, and they don’t have enemies looking for an excuse to tell on them. It never occurred to anyone to give those being hidden by the Zubrys family, including our daughter, away to the occupation authorities.

Those of us left behind in the ghetto, knew nothing about all of this.

Now it was time to save my eldest daughter Bella’s life. After many complex and dangerous ‘maneuvers’, I once again find myself in the city. And again, I am greeted with fear that is difficult to disguise, but which is also an unpleasant surprise. I am not offended - I quite understand that people are frightened. But I have to save Bella. I make every effort to overcome the fear and humiliation. After a thorough search I reach Dr. Ona Landsbergienė, an ophthalmologist. She knows me from our university days.

There were just two village women in the waiting room, holding straw baskets and wrapped in large scarves. I didn’t consider them dangerous.

When Dr. Landsbergienė came out of her office and saw me, she greeted me as if I were a regular patient coming for an appointment. She placed thermophores (special flat, round, electric heat therapy pads) over both eyes. They actually cover most of the face. While doing this, she whispered encouraging words in my ear. How kind and generous she was! I was so grateful at that moment! It was wonderful to sit with my face covered! Feeling safe and warm, it helped me regain my spirits after my experiences and humiliations that day.

When it was my turn, Dr. Landsbergienė invited me into her office, which she darkened by drawing black curtains across the windows, which was routine during a funduscopic examination, and asked how she could be of help.

She listened closely to what I had to say, gave it some thought and said without further ado: “Bring her”. Her abrupt way of speaking was characteristic of Dr. Landsbergienė, such a dear person who, unfortunately, is no longer with us. She had a rough exterior which hid a big heart and strong emotion.

And, so, there is a place for Bella. Once again, we face a precarious problem – how to get her out of the ghetto. It is now much more difficult: there are more guards, and many people are being shot near the fence when the guards realize that they are trying to flee the ghetto. The number of people in the brigades are counted, they no longer walk to work but are taken on a truck. We gave much thought to ways of escape but we came up empty handed. Then we heard about a new brigade, which is taken by boat in a separate group to the opposite bank of the Naris River, straight to their place of work. A commotion arises when crossing the river in the boat, which is purposely exacerbated. It is difficult to take a head count and that moment offers a good chance of escape – of course, with the danger of being killed by bullets fired by the guards. However, there is no other way – you have to dare to take risks.

Being in the ghetto, we don’t know if Bella managed to escape. We had no knowledge of the fate of our other daughters who were supposed to go to places prepared for them; had anyone informed on them, were they still alive?

How could I sit around doing nothing when I have no idea what had happened to my daughters? Perhaps they need me; perhaps I could do something to help them in the future if I stay alive. But, how can I escape the ghetto, and where could I hide in the forest? After all, I had exploited all the feasible and unfeasible options while looking for somewhere to hide the girls.

Eventually, when the three girls were on the other side of the barbed-wire fence of the ghetto, I came to terms with our fate and begged God, as I used to when I was a child, to not let any evil befall our girls. But I felt it imperative to go to the city from time to time, to make sure in my own round-about way, how the girls were faring.

Many in the ghetto were jealous of us for having managed to arrange shelter in the city for our three girls.

During that period, I did everything I could to advise other unfortunate mothers, who had hidden their children under lock and key, in all sorts of warehouses, pantries, enclosed yards, as ‘illegals’ and a danger to the public. I wasn’t the only one, there were others who looked for good Lithuanians who would agree to taken in and hide the children, usually each one on its own. It was extremely dangerous to shelter Jewish children so it was preferable if they actually knew them. However, most of the parents were scared to take the risk of handing their children over. Moreover, this search endangered not only their own lives but also those of the Lithuanian families to a large degree.

How could we ask people to do this? Many made an effort to compensate the rescuers with valuables. Besides, there were also Lithuanians who demanded astronomical sums for taking such dangerous steps. All our rescuers, professional Lithuanian colleagues, didn’t do it in order to get a prize. I didn’t even dare to think about offering any sort of reward.

The parents’ main problem was getting their children into the city. They could explain to the older children how to behave in any situation. Babies and children up to two or older, were taken out of the ghetto in various types of rucksacks, by people going to work. It was necessary to sedate these little ones with sufficient Luminol for them to sleep without waking up and crying. I was nervous each time in case, God forbid, I gave them too large a dose. I discovered that I had a new specialty – sedating children before taking them out of the ghetto in order to save their lives. What an awful sight it was to see them hunched over, their heads bent, limp – to make it easier to cram them into the rucksack.

And afterwards? How would those poor little ones feel waking up in a strange environment, with strangers speaking in an incomprehensible language – only God knows …..