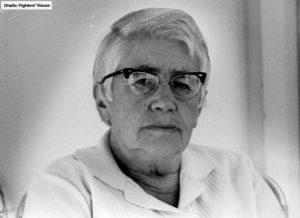

Fruma Gurevitz

When she emigrated to Israel in the 1970s, Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich), a doctor from Kaunas, took with her a lot of material on rescuers of Jews, including their addresses, that she had been collecting for several years. Some time after she settled in Israel, thank-you letters to rescuers of Jews for the lives that they had saved during the Holocaust started making their way to Lithuania. These letters were signed by Gurvičienė herself as well as the writers Icchokas Meras and Mejeris Elinas. The letters from far-away Israel were a genuine surprise, especially since they were written in the times when the topic of rescued Jews was not popular. This gesture of respect brought joy to many rescuers, or to their children and relatives, if they were no longer alive. Antanas Zubrys died in 1951, Matilda Zubrienė in 1970 and it was their children who received the warm letters of the most profound gratitude.

When she emigrated to Israel in the 1970s, Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich), a doctor from Kaunas, took with her a lot of material on rescuers of Jews, including their addresses, that she had been collecting for several years. Some time after she settled in Israel, thank-you letters to rescuers of Jews for the lives that they had saved during the Holocaust started making their way to Lithuania. These letters were signed by Gurvičienė herself as well as the writers Icchokas Meras and Mejeris Elinas. The letters from far-away Israel were a genuine surprise, especially since they were written in the times when the topic of rescued Jews was not popular. This gesture of respect brought joy to many rescuers, or to their children and relatives, if they were no longer alive. Antanas Zubrys died in 1951, Matilda Zubrienė in 1970 and it was their children who received the warm letters of the most profound gratitude.

In her article “Spring of 1944” (“1944 metų pavasaris”) in Soldiers Without Guns (“Ir be ginklo kariai”), edited by Sofija Binkienė (Vilnius: published by Mintis, 1967), Fruma Gurvičienė (Frúme Gurvich) lays bare the despair of the people behind the barbed wire of the Kovno Ghetto when, after the “children’s Aktion” in the Šiauliai (Shavl) Ghetto on November 5th, 1943, they realized that mortal danger looming, it seemed, inevitable, over all Jewish children. Sadly, only a minority of people imprisoned in the Kovno Ghetto managed to find acquaintances from before the war who would take in and hide their children.

Having survived the horrible “Children’s Aktion” in the Kovno Ghetto on March 27th and 28th, 1944, Frúme Gurvich decided to look for shelter for her five-year-old niece Naomi as well as her daughters, twelve-year-old Etta and sixteen-year-old Bella. She wandered through her home city of Kaunas, now hostile and alien, and first of all contacted her former colleagues, Kaunas doctors. Sadly, some did not have enough courage to even look her in the eye. Some slammed their doors in her face. Fruma almost succumbed to the terrible despair. But then, a miracle happened.

In her memoirs, Dr. Fruma Gurevičienė (Frúme Gurvich) wrote:

To the end of my days, I will not forget the way I was taken in by Dr. Matilda Zubrienė and her husband Antanas Zubrys. How they calmed me down and even gently scolded me, parent-like, for not coming to them straight away. I could not believe my ears. They agreed to take in one of my daughters and disguise her as a shepherdess in the countryside. I warned them, once more, that my daughters were brunettes and that they were easily recognizable. To which they answered: “Is it their fault that their hair is black?” How delighted I was to hear such warm words. How much hope and trust in humankind they brought me.

Since Antanas and Matilda Zubrys’ house stood on Donelaičio Street in the center of Kaunas, they decided to take Gurvičienė’s daughter Etta to a safer spot: their own farm in Armališkės. There, Antanas Zubrys had already been hiding Haris Goldbergas, son of a Kaunas lawyer, for a period. Those wartime days in Armališkės with Eta Gurvičiūtė and Haris Goldbergas are well remembered by Aldona Bogdanienė, daughter of Antanas and Matilda Zubrys, who is still with us today.

Dr. Fruma Gurvičienė’s risky wanderings through Nazi-occupied Kaunas in search of rescuers for her girls had a happy ending. Her little niece Naomi was with no hesitation accepted by her former course mate, Dr. Marija Butkevičienė: together with her own daughter Ona, and and her son Povilas. They cared for the little girl for some six months, up to the autumn of 1944. And, the elder daughter Bella was rescued by Dr. Ona Landsbergienė, the chief doctor at the Department of Ophthalmology at Kaunas Clinic. After having carefully listened to Fruma’s plea, she gave a laconic answer: “Let her come.” From the Landsbergis’ family home in Kaunas, Bella was moved to their summer house in Kačerginė, where she was cared for by all members of the family...

From: Defending History

Dr. Fruma Gurevich, from the Vilijampole Ghetto in Kovno, describes how she found hiding places for her three daughters with the families of doctors with whom she had studied, and how she helped other children flee the ghetto.

At long last, I managed to join the women’s brigade, which was taken to work in the city every morning. At dawn, I marched together with hundreds of women along the uneven streets of the ghetto in Vilijampole. Armed soldiers watched over us, rifles at the ready. We passed through the gate into the streets of Kovno.

The city appeared silent, still sleeping peacefully. Lithuanian children lay asleep in comfortable, warm apartments – those same children I had treated until recently, often managing to save their lives. And then, at the beginning of the war, some of their parents had indiscriminately axed entire Jewish families to death – the old, women, and babies. Right in this alley, a pile of corpses with shattered skulls was collected. Over there, on the corner, lived my sister, Emma, also a pediatrician. She had been sent somewhere. Where was she now? My mind raced … but the women in the brigade urged me to move on, so I did. Miraculously, I managed to slip away at an intersection without the guard noticing. Once behind a courtyard gate, I tore off the yellow patches. How, later on, when I fell back in line with the brigade, would I manage to reattach them so that the sentries wouldn’t notice they were missing? With my heart pounding, I wandered through the streets of this hostile city. I had actually been born here, as had my father and grandfather. I had loved Kovno! How proud I was of it! Who could have foreseen that murderous villains would live among us?

Walking one step at a time, it felt as if the ground were on fire beneath my feet… I would soon be arrested… I ended up standing in front of the small plaque of a doctor I knew well. The waiting room was full. I didn’t want to be among other patients, staring at each other with questioning looks. I continued wandering. I found the apartment of another doctor. He wasn’t home. I went to a third, then a fourth – but I was stopped at the front door, apparently recognized, and the door was slammed in my face. I was losing hope. Despondent, I gave it another try – and walked toward the ‘Green Mountain’ to Dr. Marija Butkevičienė, with whom I had studied years ago. A small, wooden house. I was sure I would fare no better. Wait – what was happening? I was received with open arms. They sat me down, listened sympathetically … (I couldn’t believe my ears), and agreed to take in 5-year-old Naomi, our youngest, the first who should be saved.

As soon as I heard that they would take our little one, I felt indescribable happiness but also anxiety. Why was I imposing such danger on these brave people? I explained that Naomi had brown hair and didn’t look like the rest of the family. Dr. Butkeviciene, her daughter Ona, and her son Povilas tried to calm me, promising that if we brought the little girl to them, they would do their utmost to hide her.

I left their modest house feeling happy and encouraged by their human kindness. But how would I rejoin the brigade to return to the ghetto? Most importantly, how would I get Naomi out of the ghetto? I would sedate smaller children with Luminol so parents could smuggle them out in backpacks. But Naomi was five, and even if very thin, it would be difficult to hide her in a backpack.

Two days later, after much planning, we decided to take Naomi into the city in a sack, under a load of potatoes.

We explained the plan to her. Naomi, tears rolling down her cheeks, said: “I don’t want to leave my mother, but I know I have to,” and agreed to sit in total silence, without moving, so as not to arouse the suspicion of the German sentry on the cart.

The fateful morning came. Dawn was breaking, the sky gray and dismal. The little girl hugged her favorite toy – Mishka, her threadbare teddy bear – and climbed into the sack, placed on the cart with other sacks and covered with straw for camouflage. The cart managed to leave via the ghetto gate. Two ghetto workers, who helped load and unload it, sat on top. They were stopped several times, but the German sentry, unfamiliar with the route, did not notice. They had agreed to stop at an address we had given, to take the girl out of the sack and leave her in the hallway.

Dr. Butkeviciene lived far from the ghetto, so we had to find another way. A pediatric consultation center not far from the ghetto, where a medic friend, Yelena, worked, would help. I had met her previously and reached an agreement: as soon as the child reached the center, she would take her to Dr. Butkeviciene. Early mornings, no strangers were around, and no one saw Naomi crawl out of the sack. Those of us back in the ghetto had no knowledge of Naomi’s fate, though the Butkeviciene family surely worried.

Their apartment was low, with many neighbors, some Nazi supporters, some curious. Danger was constant – for Naomi and the Butkeviciene family.

Meanwhile, I needed to place our other two daughters. Again, I wandered friendless, shivering with fear and mental stress. Knocking on doors, people were frightened by my presence, seeing me as a potential danger.

So much unpleasantness, heartbreak, and humiliation! But the main goal was saving the girls. I could not let their lives fall into Gestapo hands.

I considered using morphine and fast-acting poison for myself and the girls, as a last resort. But I did not have the strength to do it myself.

I continued my own ‘Via Dolorosa’, zig-zagging through the city streets, each passerby seeming a potential enemy. Eventually, I reached Dr. S., a colleague who had graduated a year after me. She welcomed me but began complaining about her inability to find a cleaner. I suggested my eldest daughter, 16, could clean for her. “Good,” she said, “but there’s no room for a bed because of our large dog and an unwilling landlord.” A small inconvenience in the face of life and death. I left, broken but still determined.

Dr. Matilda Zubrienė, on the same lane, had previously been absent. This time, she and her husband welcomed me warmly, comforted me, and promised to take one daughter, arranging for her to work as a farm girl. I warned that our daughters’ brownish hair might give them away. They responded: “Is it their fault that they have dark hair?” Such confidence inspired me.

Back in the ghetto, I worried how to join the brigade without the sentries noticing. These situations could fill books, but this was reality – every escape attempt was terrifying.

Etta, 12, was next. She would escape as a worker in the brigade. Dressed in a long coat over her short coat, scarfed, wearing high-heeled shoes, and with a knapsack disguised as a bag for shavings, she followed the instructions I gave. She remained silent, mature beyond her years. The sentries ignored her, and she found the people who promised shelter.

Bella, our eldest, came last. After searching, I reached Dr. Ona Landsbergienė, an ophthalmologist. Only two village women were in the waiting room. Dr. Landsbergienė welcomed me, covered my face with thermophores, and listened carefully. She said simply: “Bring her.” With this, Bella had a place.

Getting Bella out was more dangerous than ever. Guards now shot anyone attempting to flee. A new brigade, transported by boat to the opposite bank of the Naris River, offered the only opportunity. Risking bullets, we had no other choice.

When the three girls were finally safe on the other side of the barbed-wire fence, I prayed God would protect them. I still visited the city to ensure they fared well.

Many in the ghetto envied us for arranging shelter for the girls. I also advised other mothers on finding Lithuanians willing to hide their children. It was extremely dangerous; some people demanded payment, but our rescuers did it selflessly. Older children were taught to behave appropriately. Babies and toddlers were sedated with Luminol to sleep during transport. I discovered a grim specialty: sedating children to save their lives, seeing them limp and hunched over, ready to be hidden. Only God knew how they felt waking in strange surroundings.

Translated from : CET - The Center for Educational Technology-Fruma Gurevich testimony,