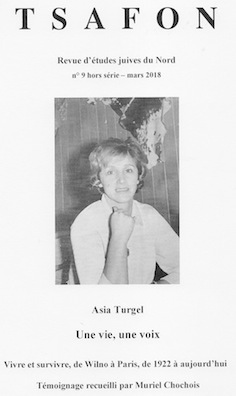

Asia Turgel

Asia Turgel was born in Vilna, then a Polish city, in 1922, to Shavouot, third child of Izrael-Wulf, electrical engineer trained in Saint Petersburg, and of Pesia Bulkin, the aunt of actor Joseph Bulov. Asia has three brothers, Yankel, Aron and Moizesz. She studied in the Yiddish language, then attended a Polish public school for Jewish children. The world of Asia is the ancient center of Wilno, frequenting Jewish friends, activities that take place in Jewish sports clubs and cultural places, when Poles and Jews live in two separate universes. It's a life punctuated by celebrations and their preparations, in a practicing family, but like Wilno, not fanatic, to use Ms. Turgel's words. It's a life fueled by music, dance, and above all, above all, readings. In September 1941, Asia is reading, in Polish, Gone with the Wind, seated in the middle of their packages, when it's the Turgel family's turn to join, surrounded by Lithuanian militias, the ghetto. Working in a workshop for the rehabilitation of German uniforms, the Feldbekleidungsamt, installed in its former school, on Bakshta Street, Asia pursues some cultural activities, to forget what is her permanent fear: not finding, on returning from work, her mother and niece, Rivka, the daughter of Yankel, who lives with them.

Asia Turgel was born in Vilna, then a Polish city, in 1922, to Shavouot, third child of Izrael-Wulf, electrical engineer trained in Saint Petersburg, and of Pesia Bulkin, the aunt of actor Joseph Bulov. Asia has three brothers, Yankel, Aron and Moizesz. She studied in the Yiddish language, then attended a Polish public school for Jewish children. The world of Asia is the ancient center of Wilno, frequenting Jewish friends, activities that take place in Jewish sports clubs and cultural places, when Poles and Jews live in two separate universes. It's a life punctuated by celebrations and their preparations, in a practicing family, but like Wilno, not fanatic, to use Ms. Turgel's words. It's a life fueled by music, dance, and above all, above all, readings. In September 1941, Asia is reading, in Polish, Gone with the Wind, seated in the middle of their packages, when it's the Turgel family's turn to join, surrounded by Lithuanian militias, the ghetto. Working in a workshop for the rehabilitation of German uniforms, the Feldbekleidungsamt, installed in its former school, on Bakshta Street, Asia pursues some cultural activities, to forget what is her permanent fear: not finding, on returning from work, her mother and niece, Rivka, the daughter of Yankel, who lives with them.

September 23, 1943 is the only date Asia remembers. The ghetto is liquidated, men and women are separated. Asia will never see her family again. The train takes her to Kaiserwald camp, from where she will then be transferred to Stutthof camp, then to Polte - Magdeburg camp. Escaping execution by fleeing, with other prisoners, from the ravine where they had been taken, she arrived in Paris in July 1945.

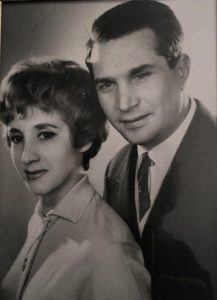

It was in a reception center for deportees, near Grenoble, that she met Maurice Miedrzyrzecki a few weeks later. Asia and Maurice get married at the town hall of Corenc on August 25, 1945. They have a son, Yves, named in memory of his grandfather Izrael-Wulf, then a granddaughter, Deborah. Maurice Miedrzyrzecki died in Paris on June 23, 2013. And Léna, the daughter of Deborah, the great-granddaughter of Asia Turgel, was born on August 23, 2013.

Muriel Chochois has edited a book which is the fruit of regular meetings, having been the subject of notes or recordings, and this since April 2009. What Asia carries in these few pages is a life story, a Jewish life, and its transformation, from 1922 to today. It is the story of a young girl with a normal life, who knows hell, then finds a normal life. These two "states" live in Asia, bringing her to look at the world with kindness and extreme lucidity, as if she were looking beyond people and the horizon that is ours. More than a testimony, it is an interior experience that Asia and I tried to write, by accompanying the reader in his understanding of the world crossed and by opening doors to other creations.

Translated from: Tsafon

Muriel Chochois eulogy upon Asia Turgel death

Asia, dear Asia…

“There are so many things that I’d like to forget”, “I don’t want to not remember” … How many times, in our many discussions, did you say these words? Your wish to forget and yet your need to not forget your relatives. Your memories were there even though you wished to forget. You needed to honour your relatives and to show that you were not just a victim, that your history was not summed up by what you lived through in the ghetto and the camps. There was your dear Wilno, the family apartment on Sawitsh street, the shabbat table, the majestic beard of your Zeyde, your grandfather Mordekhai. There were the preparations for Pesach and the bedazzled eyes of the neighbourhood children in front of the bakery shop window where matzot were being made. Also there was Jules Verne, Saturdays at the theatre with Pesia, your mother, your pride when people spoke of your father saying “Ah Turgel, Elektrotekhniker…”, the summer months in a rented house a few kilometres away on the banks of the Vilya, the Shimen Frug school, piano and dance lessons.

And then came September 6, 1941. In the months and years that followed you saw what nobody should see. Humiliations and shame when your family had to move to the ghetto. Shame in the camps when as a prisoner you were addressed with the familiar “you” and you had to accept everything that happened. Shame and denigration too after arriving in Paris in the summer of 1945 when a Jewish lady asked you to come back the next day to clean her windows.

The dialogue that we tried to build together was to counter the shame, to bring back dignity… “to be able to look yourself in the mirror”. Saying that, I remember you telling me of the only time that you actually looked in a mirror in the camps. It was at Magdebourg, in a factory where, without protection, you dipped ammunition into an acid bath. A friend held out a piece of mirror to you… you were yellow. “I was already gassed” you said. Facing such stories, and while I was learning everything from you, I knew that I had to show you your dignity, your worth to yourself and to others. “On our arrival the first day at Magdebourg, an SS came and asked for twenty people to go to the shower. I thought it was to die. I did not want to die but I did not want to wait while the others left to be killed. I immediately volunteered to go.” Dignity, keeping your strength, and helping others as much as you could; you persuaded a friend to eat her bread little by little… showing that it’s always possible to keep a free will.

Your free will and your resistance through revolt. In your words, Asia, there was not the easy message that others may have written. What we heard were the whys. : “Why six million Jews? there were thieves, of course, but not six million killers.” “Why my father? He was a good Jew, he put Teffilin and prayed every day.” And you got angry with me about these questions : “You’ve done long studies, you explain it to me” you said. Rabbi Pauline Bebe, in the post-face of the book describing such moments, wrote : “These questions must not find answers, as any answer would be to justify the impossible, the unbearable and the iniquitous.”

Your free will and your resistance through revolt. You were proud to carry your family history in your name. “Asne Turgel, I am Asne Turgel !!”, you shouted when one of your old school teachers recognised you in August 1945. That meeting allowed you to state forcefully your name, your real name, after having had to use other names when you thought you were “the only Jew in the world to stay alive”… And the names of your loved ones came back… “When we made a family festive meal at home we were fifty people… I am the only one to have survived” you said... Today it is not possible to name those fifty close relatives… Today may the memory of Izrael-Wulf Turgel and Pesia Bulkin, your parents, Yankel Turgel, Aron Turgel, Moizesz Turgel, your brothers, and Rivka Turgel, your niece, and our dear Maurice, an eydeler mentsh, be by your side.

With my love… Muriel (translated to English by Mark Salik)

Holocaust survivor Asia Turgel dies/ Times of Israel, 29 April 2020,

In her interviews, Asia Turgel regretted that no one can understand the reality of the camps, her pain and her fear since her liberation.

Asia Turgel, survivor of the Shoah, died on Tuesday in Paris at the age of 98, reported on Twitter Sophie Nahum, director and author behind the multimedia project "The Last" , who had met her in this frame.

Born in 1922, Asia Turgel, originally from Vilnius, at the time in Poland, was taken to the city ghetto in September 1941, before being deported to the Riga-Kaiserwald concentration camp, then to the Magdeburg camp. , first dependent on the Ravensbrück camp before being attached to Buchenwald in September 1944.

“When we got to the Block in Kaiserwald, we were told to leave all the luggage. We entered the shower by the door, we came out by another. We were given other clothes. We only kept her shoes. And I had no more papers or photos. It was finished. I had no more name, no more age, ” she explained in 2009 to historian Muriel Chochois.

Asia Turgel managed to escape while being evacuated from the camp for a death march, reported Simon Malkès in his book Le Juste de la Wehrmacht .

After the war, arrived in Paris, she lived in a house for deportees, where she met her husband. They will become parents of a son.

In her interviews, Asia Turgel regretted that no one could understand the reality of the camps, her pain and her fear since her liberation.