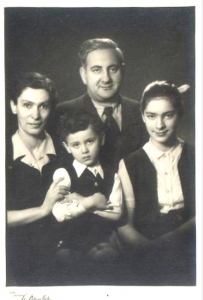

Ya'arit Glazer- Krakinovsky and Discant families

My name is Ya'arit Glezer – Krakinovsky, and I was born in Kaunas in 1947. My parents were also from Kaunas. I have one younger brother. We lived in the very center of Kaunas on Laisves Aleja. It was a 3 room apartment where 3 families lived together. All the neighbors were Holocaust survivors whom my parents let in since they had no family left and no place for them to live.

My mother, Rivka Discant, was the eldest in the family and she had three younger brothers.

Before the war she went to Italy and there in the university of Pisa she started to study medicine but was forced to leave Italy by Mussolini.

My father and my mother did not have the chance to get higher education. In 1941 my father was 18 years old and would have started to study but the German army invaded Lithuania and he did not manage to enter the college. Only years after the war did they go back to study. I remember how we graduated together – I finished school and they finished college. I still remember how my father did all the drawing for her and she wrote the compositions in Lithuanian for him.

They both worked at the tobacco factory in Kaunas, and in our h ome you could always find cigarettes because they were really heavy smokers.

ome you could always find cigarettes because they were really heavy smokers.

I went to school in Kaunas and the teaching in my school was in Russian. At home we spoke Russian and my parents between them spoke Yiddish, but when they did not want me to understand what they were talking about they switched to Hebrew.

Then we moved to another apartment that was just across from the War museum (Karo Muzejus), and there we used to spend a lot of time. In winter the central X-Mas tree was also there as well as a snow hill for sledding. Not always did we have a toboggan so we used plywood sheets and enjoyed every moment of sliding.

I think there is not a family in Kaunas that the kids were not photographed on or near the lions. Many years later when I visited Kaunas I could not resist and took a picture near the lions (well, I could not climb them at my age).

After graduating school I went to the university to become a teacher. I worked at a high school for 35 years and now I am retired.

After graduating school I went to the university to become a teacher. I worked at a high school for 35 years and now I am retired.

Our family was not religious, and we celebrated the Jewish holiday in a very unorthodox manner. During Passover we had matzos but did not observe the necessary procedure.

I also remember that during the festival of Succot (Tabernacles) we, the youngsters, would go to the synagogue and there they gave us flags richly ornamented with gold, silver and some writing. I remember I came late and there were no more flags left. So I was given a very simple flag – blue and white. Sure I was very disappointed. And then my mother very quietly explained that I got the most precious flag – the flag of the State of Israel. That was I think the first time that the idea of going to Israel started to sound audibly in my presence.

The holiday of Hanukkah was spent with friends and traditional "latkes" were prepared. We played the "spinning top" and our parents sang the Hanukkah songs in Yiddish and Hebrew. But along with that in our family X-Mas was also a very special day. On that day we would go to the Ninth Fort and meet there the few escapees that were still alive. Then those who came from other towns joined us around the table and they were raising memories – the sentence "and do you remember…" would open some more memories.

And here I have to explain the meaning of my name because it sounded very

strange back in Lithuania. But to do so I will have to go back to the story of my parents before and during the Holocaust.

My maternal grandfather Moshe Discant was a Hebrew teacher and a poet.

The poems that he wrote in Yiddish and Hebrew described the life of the ghetto prisoners, and his poems were known in the ghetto. Some of them were saved and published after the war. My mother graduated from the Hebrew school so she spoke this language freely as well as Yiddish which they spoke at home.

With the beginning of the war my father's and my mother's families were imprisoned in the ghetto. Both my grandmothers and my maternal grandfather were killed. Two of my uncles – my mother's brothers fell in the ranks of the Red Army - Isaak Discant in the first days of the occupation and Aizik almost at the end – in 1944 near the town of Taurage

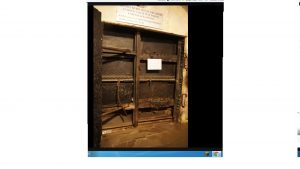

My father and my uncle Aba Discant were both caught when they were on their way to join the partisans in the forest. After being tortured in the prison they were sent to the Ninth Fort. There comes the story of their remarkable escape when all the 64 inmates whose work was to dig out the bodies of the murdered from the pits and burn them, succeeded to run away. The plan was unbelievable but against all odds it was carried out. My father Pinia Krakinovsky was one of the key figures in performing the preparation - he was the one who drilled the holes in the metal door. He worked long hours during the day when the prisoners were in the field outside – he pretended be sick which was also dangerous because the Germans could kill him any day. But by 24 December he finished his work – he drilled about 350 holes and that made it possible for the prisoners to leave the fortress.

After the escape my father and uncle joined the partisans and my mother joined them in the forest later.

When I was born they gave me the most meaningful name because ya'ar in Hebrew means forest.

When 10 years later my brother was born he was named after our grandfather Moshe Discant.

I really believe that sometimes the name of the person influences his fate. I think that is why I became interested in what happened to my family during the Shoah. As I read somewhere in every family of Holocaust survivors one of the children becomes a memory candle. So it happened to me. But to start to really learn about the details I began much too late when there were not many people left to ask questions.

I began to give lectures, actually I was telling the story of my family during the Holocaust. But then I understood that it was not enough so I started looking for material about the Shoah, and the more I read the better I understood that I have to know much more. I joined different courses to get more information. I remember the first group that I had was to accompany to Poland as a guide. A few years later I began to work as a lecturer with groups of students coming to Israel to participate in seminars about the Shoah. And then I was invited to hold seminars for teachers in Lithuania. I still remembered Lithuanian so this was the language of the seminars though the materials that I prepared about the Vilnius and Kaunas ghetto were in Russian.

Every year there is a group of second generation of survivors – people whose parents were Litvaks - come in September to Lithuania and visit Paneriai and the Ninth Fort.

Since 1989 when I first came back to Lithuania I have seen many changes in the attitude of people to the problems (and there are many) of the Shoah. And I want to cite the words said at one of the memorials that "Lithuania will not be free of the past until she acknowledges that it happened."

Today I am a proud grandmother of 5 grandchildren – 3 girls and 2 boys, and my eldest granddaughter is joining the army in a few months. A few years ago we visited Lithuania – my elder son with his wife and children, and I am glad that I could take them to all the places that connect me with Lithuania.

The Escape - A Hanukkah Miracle - By Ya'arit Glazer

This year as ever, Hanukkah falls on Christmas or perhaps vice versa, Christmas on the days of Hanukkah. I remember what father would say, not once, not in order, only on rare occasions and on Christmas days, when all our friends would come to Kovno and meet at our house. Hence, I also do not continue in a certain order - what is in front of my eyes at that moment is what I will write about.

‘Now, it is your turn to go out into the woods,’ said Chaim Yellin, a writer, Zionist activist and reporter for the Der Emes newspaper and underground commander of the Kovno Ghetto.

‘Are you ready?’ he would ask. They were ready, of course. Everyone's dream was to be with the partisans, hold weapon in hand and fight the Germans. I'm sure Abbale remembered the night before. A cold and dark evening, it was. The room is lit by a candle and shadows move on walls following the movement of people. Family members sit next to each other in the small room, huddled together - my mother, her younger brother Abbale, Grandpa Moshe, Grandma Guta, and I - only that my own shadow is not reflected on the wall. Two brothers are missing - Yitzhak a fighter in the Red Army, and Isaac who joined the soldiers of the Lithuanian 16th Division.

The room’s atmosphere is heavy even though not a single word is spoken. Young people look each other in the eyes asking ‘Who will be the first to speak? ’Who will announce the decision that had been so difficult to make.’

I am tense as well. What did they decide? What do they want to talk about, and how will the grandparents react? I'm almost sure I know what the conversation will be about. I glance slowly at everyone sitting around the table; on everyone's face I see a similar expression of pain, of worry, but of determination as well. Abbale, the younger brother, addresses the parents in a strangled but resolute voice and says: "Dear parents, what we want to tell you is not the result of a sudden impulse. We debated a lot and still came to the conclusion that we should not sit here in the ghetto without acting and wait for our last day. We arranged with the members of the underground that, next week, we will go to the forest and join the partisans."

I keep listening but at the same time think about the arguments they must have had: ‘How to tell the parents? ‘How to announce the decision?’

Abbale continues: "Just so you understand it's up to you, since we will not leave if you object. It is clear to me and my sister that you would be left here alone and therefore your word is decisive."

Deep down they know what Father and Mother’s answer will be, but need to hear it from them. "Father, the poems you write, are read by many; they give them the courage and strength to keep fighting to survive. We too want to rise against the occupiers, and if we are sentenced to die it will be with weapon in hand."

I am overwhelmed by their words. I shout at them, "How can you leave the old people alone? Who will take care of them? Who will protect them? I know what will happen to them!" But of course they don’t hear me. Abbale continues: "Who will take care of you? Who will protect you?"

What, he heard me? That's exactly what I shouted.

At this moment my mother, Rebecca, joins her brother, saying, "We can’t sit here arms crossed when our souls are burning, seeking to act; even the forest is dangerous, even there death lurks in every corner, but at least if we are doomed to die then we will die like soldiers, like human beings."

Is this my gentle, quiet mother who demands to go out into the forest and become a partisan?

I am still in the little room. Two old people sit hugging each other, looking each other in the eyes. "So, Guta, we stay together. It's better the kids leave and don’t witness our last moments." Grandma Guta was sent to Stutthof and Grandpa Moshe, the poet and writer, the beloved teacher, perished in one of the camps.

Three days later, a group went out, among them Abbale and another three friends, one of whom was my father, Pinchas Krakinovski. They were on their way to the forest but were caught on the way and sent to the Ninth Fort - the Death Fort.

The truck leading them stopped at the gate and they got off. It was already evening, heavy and cold rain fell, as happens in the autumn months in Lithuania. In front of them stood a German officer and next to him a translator, probably one of the prisoners.

From the German’s long speech, they realized they were ‘lucky’ and had arrived at a time when there was a shortage of workers in the camp, hence they were sent to join the Sonderkommando team ‘cleaning’ the pits. They still did not know what it meant, but already the next day, when they were taken out to the field the kind of work involved was made clear. Their task was to get corpses out of the pits and transfer them to bonfires that burned day and night.

The fort contained prisoners of war, all Jews, and prisoners from the ghetto - a total of 64 people.

The ghetto’s youth started looking for ways to escape and devised several plans, but rejected them all as unrealistic. Meanwhile, a new, completely different plan was brewing, with only a few people knowing about it.

A round stove stood in the hallway. The prisoners would sit around it, talk and even sing. Coal for heating was plentiful. This is where connections began between the two groups - between the POWs and members of the ghetto underground.

During the singing and conversations beside the stove, the young people would speak quietly so as not to be heard. The Germans were also happy - if they sing they are in a good mood, and that means we don’t need to fear them.

Alexander (Sashka) Podolski "The Brigadier" and Abbale went up the stairs to the second floor and Sashka led him into a tunnel laden with firewood. They finally reached the end of the tunnel and stopped at a heavy iron door. Abba then whispered, ‘You can go out through this door...’

Many questions disturbed their peace. How do you open the door? Who will do it? All these questions did not let them fall asleep.

A few more days passed and Abbale decided he knew with whom to start - with the underground members of the ghetto, of course. He turned to my father Pinya. They were members of Hashomer Hatzair and were also in the same nucleus. Abbale also knew that Pinya had helped his father in the locksmith shop and was therefore skilled at working with metals.

When approached, Pinya immediately agreed and his only question was - when do we start? He also explained what tools he needed. The other problem was also solved - the Germans allowed two prisoners to stay inside the Fort if they had the doctor's permission, thus giving Pinya an opportunity to stay inside the building. On the first day, my father received permission. The next day he once again had to receive permission from the doctor to stay in the building. The doctor’s face showed complete lack of trust, but he again gave his permission. This went on for several days, and every day Dr. Nemionov’s face grew darker and darker. There came the day when he could no longer remain silent. "I do not know what power you have that all the prisoners give up their free day to you again and again, but I see that you are not in such a terrible condition." Of course, it was not yet time to tell the truth.

The work in the tunnel continued. Pinya drilled hole after hole. Inside the tunnel it was quiet as if underground. His knee wore out and his hands were scrapped to the bone, but he kept drilling.

The prisoners were not yet aware that a plan had taken shape. But came the day when everything was ready. Pinya drilled 314 holes. All that was needed now was a light blow on the door and the hatch would open. The hatch was ready, even a few days before the set date - December twenty-fourth - Christmas.

In the evening after the work day, everyone gathered in the hallway. Mishka "The Vagrant" organized the prisoners of war and formed a choir to sing Russian songs and even gypsy romances. Mishka danced a sailor’s dance.

In the evening after the work day, everyone gathered in the hallway. Mishka "The Vagrant" organized the prisoners of war and formed a choir to sing Russian songs and even gypsy romances. Mishka danced a sailor’s dance.

Years later, my father would tell that such a performance would not have embarrassed the Bolshoi Group.

The Germans were pleased, and said they would keep their promise to give two more free hours in the morning. Morning came and the prisoners in all the cells awoke. They got up and stood by the bunk as in routine evening checks. The initiators then explained to the prisoners the rules of conduct during the escape. Meanwhile, the organizers were busy with final preparations. They prepared a ladder of ropes, and in the cells, divided all the prisoners into groups of ten.

They covered the iron stairs with coats to prevent noise. Groups of ten were organized and stood ready. Sashka disappeared in the fog. He returned a few minutes later - but for Abbale and Pinya time stood still. Slowly everyone left the floor, went up to the second floor, crawled through the hatch in the door, went through the second tunnel, and went out.

The cells were silent, and in the corridor only remained a painting by Anatoli Garnik- ‘the finger’ - a farewell gift to the Germans.

Outside the building, the prisoners' paths parted. Most of the prisoners decided to look for partisans. Others returned to the ghetto and from there were transferred to the forests and joined the partisans.

Written by Ya'arit Glezer