Pesah (Petya) Joselevich

My father Shimon was a printer by profession and owned a printing house until the Soviet regime began; my mother Lea, née Shames, helped him in the business. My sister Chana was born in 1932 and myself on 29 April 1940.

Although I remember very little of our life in the ghetto, the constant feeling of hunger and fear stayed with me for a long time. My father used to go out of the ghetto under escort to work in the printing house. My mother worked in vegetable gardens and from time to time, risking her life as she did so, she used to bring in some vegetables. Usually she came back with little frozen beetroots, which I used to call 'mamalada', as they reminded me of the sweets known as 'marmalade'. On one occasion, Mother brought a cucumber from the vegetable garden and fed it to me. I fell ill with dysentery afterwards and she had to carry me over the bridge to the 'Small Ghetto' to see the doctor. By the time we reached him, I had already turned blue and was virtually dying. The doctor had no medicines but he gave me a direct blood transfusion using Mother's blood, and so saved me from certain death.

After miraculously surviving all the previous 'actions', during the 'Children's Action' we all hid in a tunnel which my father had already prepared beneath the cellar. On that day I can vaguely remember looking out of the window and seeing buses drive past with windows painted white.

On 27 March 1944 my father did not go out to work, but instead we all clambered into that tunnel. As a 4-year-old child I remember shouting out, because there was so little air to breathe and it was so dark and frightening. My mouth was being held shut, I think by my sister. Father stayed behind a heap of rubbish outside our hiding place. On that occasion they did not find us, but by then my parents realized that it was only a question of time before we would be taken off to our deaths.

My parents were looking for a safe shelter for us for a long time. Eventually my father made contact with one of his pre-war colleagues, Yulia Vitkauskiene. She got in touch with another of father's colleagues, Pranas Vocelka, who had a Jewish wife called Freiga in the ghetto. Mr Vocelka had already helped many people find refuge and agreed to keep me for a while. Yulia then made contact with Elena and Mikas Lukauskas, also printers by profession. They lived on Green Hill and had no children of their own. Elena was a well-known chess player, the women's champion of Lithuania.

I was frightened of Germans and knew that we had to hide from them. One day Father came home with an Austrian soldier, who agreed to help carry me out of the ghetto. When I saw the soldier in uniform I scampered away under the bed and no amount of persuading was enough to drag me back out again. So his first attempt to get me out of the ghetto failed. Mother decided that I should be given a sleeping pill, and after that I was hidden in a sack of hay, loaded on a cart and it was agreed that the woman driving the cart would take me out through the gate. Just as we were going past the guards, a piece of straw tickled my nose and I sneezed: the cart driver turned back and threw the sack down near our house. On the next occasion I was given a double dose of sleeping pills and I was dead to the world as I slept. All I remember next is being on the sofa in Vocelka's home.

From there I was sent on to join the Lukauskas family. All those who helped rescue me did so, risking their lives, out of kindness, not for payment. How they managed to get my sister Chana out of the ghetto I do not know. Finally, she turned up too at the house of the Lukauskas family.

I still have a letter our mother wrote to my future rescuers, whom she did not know at the time. Elena Lukauskiene eventually returned it to me after the war. My mother had written:

To strangers, who are now close dear friends! I do not have enough words to express my gratitude to you for your humane deed. We are wretched, but at the same time happy in the knowledge that at this time, when the human race is behaving in a bestial way, good and warm- hearted people have come forward to save our children . . . We are not religious ourselves and it is not important to us in which religion our children are brought up . . . Death is no longer frightening for us, because we know and shall remember that our children are in safe hands. One last request: if we do not survive, please tell our children, when they grow up, that their parents were killed by beasts in human form and that they were honest, hard-working people, who lived only for their children . . . May fate be more merciful to all of you than to us. Our gratitude to you knows no end . . .

At that time I only spoke Yiddish and it was not easy for the Lukauskas family to cope with me. Towards the end of the war the Germans started taking Lithuanians to make them serve in their army, and one day they turned up at the Lukauskas home. Mikas Lukauskas ran to the attic to avoid mobilization. At the time the family had a large bulldog. Elena threw me on to the bed and told me to say nothing or just to call out 'Mama, Mama!' She put my sister on the couch and said that she was ill. The Germans were terrified of illness and gave her a wide berth. The Germans were about to go into the kitchen, when the dog threw itself at them. They wanted to shoot it but Elena Lukauskiene stood between them and the dog and said, 'Shoot me!' The Germans went off after that, saying, 'Don't get involved with this crazy woman.' Apart from my sister and myself, Lukauskas was also sheltering a Ukrainian POW, whom we called Opanas, in their attic. The entrance to the attic was via the kitchen. If they had found the prisoner and Mikas, we would all have perished.

On the first day after the liberation, Mikas Lukauskas smacked me and said, 'Cry as much as you want, but I'm now going to teach you to speak Lithuanian come what may!' Before that all I had ever come out with in response to his requests to speak Lithuanian was three words of Yiddish, 'Ich vil nicht!' ('I don't want to!'). His insistence helped, and I instantly started talking Lithuanian.

Immediately after Kaunas had been liberated, father's brother, David Joselevich, went seeking for surviving relatives. He had been hidden during the occupation by a Lithuanian woman. When David came to fetch us, Elena Lukauskiene cried because she considered us part of her family and was sad to part with us.

My uncle David was also looking for the children of his sister, my aunt Masha. Masha Joselevich-Garonas and Bentsel Garonas had two sons: Hirsh born in 1932, and Meir (Meika) in 1936. Before the war their family had been on the NKVD list for deportation to Siberia. When preparing for their departure they had stamped all the items of clothing which they were planning to take with them. Eventually the Soviets failed to deport them.

Meika was taken out of the ghetto twice in a sack of potatoes. The first time he started crying near the gate and had to be brought back in again; the second time he was given sleeping pills and the escape went according to plan. He had been entrusted to a Lithuanian family for payment, but the very same day they turned the little boy out into the street and Germans picked him up. The people who saw him being arrested tried to convince the Germans that the little boy was Polish (he spoke Polish fluently), but the Germans checked, and took him away. After the war David managed to find the Lithuanian who had abandoned Meir to his fate. He also found Meir's garments which the parents had stamped with his name. The Lithuanian confessed that he had turned in the small boy and he was eventually convicted.

The eldest brother Hirsh was taken to Auschwitz with 130 other Jewish children from the Kaunas Ghetto; only twenty of them survived. He was liberated by the Americans at the end of the war.

My aunt Masha had been killed by a Soviet bomb in Poland after the Stutthof concentration camp had already been liberated. Bentsel Garunas survived Dachau but died a year later, and Hirsh was taken in by another uncle, Moshe Joselevich, who had also returned from concentration camps. Hirsh died in Vilnius in 1987, aged 55. His wife Lyuba and daughter Masha Brener (Garon) live in Israel.

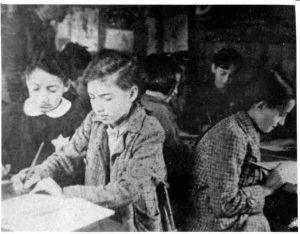

After my uncle found us, I was sent to a Jewish kindergarten and my sister started attending school. I remember that we, the children at the kindergarten, were all fearful. On one occasion there was a fire near the kindergarten and some firemen turned up in helmets, which were trophies captured from the Germans. The children were terrified at the sight and it took a long time to calm us down.

A few days before the ghetto was disbanded our father was taken out to work with the rest of his team; no one ever saw any member of that team again.

Mother was transferred to Stutthof and took part in the 'death march'. In the end she fell ill there with typhus and was abandoned in a hut to die. Thankfully she had not fallen ill on the way, because the sick had been shot on the spot during the march. Soviet soldiers found her in that hut and delivered her to an army hospital, where she took a long time to recover. Mother returned to Kaunas a good deal later and took us back from my uncle's flat.

For a long time after the war, in nightmares I saw different pictures from our life in the ghetto. Whenever I described the nightmare to my mother she would say to me, 'This is how it was and how it really happened.'

Apart from my sister and myself, Mother also took in an orphan boy, Yehuda Edelman. My mother had met a distant relative of hers in the Stutthof camp and they had promised each other that whoever survived would take care of the other's children. Yehuda, born in 1939, had been taken in by a shoemaker, who had a cobbler's shop in a basement on Laisves Avenue, where he and his family and little Yehuda, renamed Algis, lived. My mother found Yehuda and brought him back home after paying Liuda Kibartiene, the shoemaker's wife, 8,000 rubles, an enormous sum of money in those days, in return for the cost of looking after him during the occupation. To be able to do that, Mother had sold our house in Viekshniai.

Mother now had to look after three children on her own. She moved to Vilnius and worked there as a proof-reader in the publishing house, from which she had been dismissed as an 'unreliable' element. Next she found a job in the printing house. The four of us were living in one room attached to the printing works. We children slept in one bed and sat on wooden boxes instead of chairs, we had no furniture.

Mother was a very strong woman. Despite all that she had suffered and lost, she kept her spirits up and never lost her will to live. She earned her livelihood and looked after us as well as she could; we had clothes on our backs and did not go hungry. Yehuda and I were going to kindergarten, while my sister Chana went to school, where she did well at her studies.

Mother knew that Yehuda had relatives in the United States. She managed to find his uncle, the well-known Rabbi Soloveichik. In 1946 Mother paid a Polish woman, who under- took to take Yehuda to Poland and send him on from there to the United States. I remember how we went to see Yehuda off at the station and how he left with this woman sitting in a goods truck. He just disappeared, there was not a squeak out of him until Mother received a letter from a children's home in Prague, where Yehuda had ended up for some reason. She managed to contact some people in Israel, and via them Rabbi Soloveichik. Eventually, Yehuda reached his uncle that same year; it turned out that when she had sent him off to Poland, Mother had sewn her address and the address of the uncle into the lining of Yehuda's coat. Mother learnt that Yehuda had arrived safely when she received an encoded telegram from the Rabbi. She gave a sigh of relief after that, knowing that the promise given to Yehuda's mother had been kept.

Unfortunately our tragedies did not end; in 1946 my sister Chana died from meningitis.

After finishing school I naively tried to gain a place at the Leningrad Polytechnic, but naturally I did not get past the admis- sions committee, I was after all an 'unreliable element'. I graduated from the Vilnius Polytechnic Institute as a mechanical engineer. In 1966 I married a young physician, Vita Izraelyte. My mother died in 1987. In 1990 I went with my wife and two daughters to Israel. Both of us are working here in our professions.

Yehuda Edelman studied to become a rabbi, like his uncle. He has nine children; one of them lives in Kiryat Sefer in Israel. Whenever he comes to visit his son, we meet up with him and remember old times. Yehuda says that he no longer remembers anything connected with the war. He considers that my mother saved his life and there is a good deal of truth in that.