Strashun Library

The scholar and philanthropist Rabbi Mattityahu Strashun inherited a library from his father, Rabbi Samuel Strashun, to which he added his own collections. With all his sons tragically passing away in their youth, Mattityahu Strashun decided to bequeath his library to the Vilna Jewish Community. He situated the library in a house on Glaziers' street, registered it in the name of three of his colleagues, and fixed a salary for a supervisor. A catalogue entitled Likutey Shoshanim (A Gathering of Roses) from the end of the 19th century listed some 5,700 works, but the number of books and periodicals in the library was much larger, as all the editions of each journal appeared under individual titles. The library had dozens of incunabula (ancient and rare manuscripts), hundreds of volumes of responsa, and 1,000-2,500 books of Judaica in various languages. Those in charge of the library debated whether to allow access to the library by the general public out of fear that the secular books would "increase the abandonment of the Torah," but in 1893 they succumbed to pressure and opened its doors.

In 1901, the library moved to a building erected especially for it next to the Great Synagogue, uniting with the S.Y. Finn Library. The Russian authorities allowed it to open on condition that it did not house Polish books. The library was kept open on Sabbaths and Jewish holidays, except for the "Days of Awe." In 1909, the library was described in the Vilna newspaper Echo of the Times as "the spiritual centre of the all the wise men of the time, of all the young people that yearn and thirst for the wonderful past, of all those that seek the word of God and the wisdom of the Jewish people throughout generations and time. The spirit of the Jewish people flickers between the walls of the Great Synagogue, and those who enter it feel part of a genuine national Jewish atmosphere."

Most of the educated people in the city bequeathed books to the Strashun Library. The Vilna University Library also gave many books of Judaica to Strashun. In 1928, the Library contained 25,000 titles, and in 1931 – some 33,000.

From: Yad VaShem

From “Lekutei Shoshanim” until the “Paper Brigades”: The Strashun Library, Vilna.

— Frida Shor, Ariel University

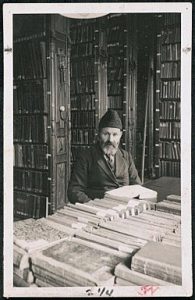

Greetings -- I’ve been given 15 minutes to speak about the Strashun Library, which operated for more than 40 years. Just as one could summarize the 40 years the Israelites wandered in the desert with two words: “Matan Torah” [The Giving of the Torah], so I will too characterize the Strashun Library with two words: “Mikdash Me’at” [The Temple]. For this is the same way in which its chief librarian, Khaykl Lunski, regarded the library: “This is the temple, in which I was educated and witnessed the happiness of my life… sometimes, when I would pass amongst the bookshelves and glance at the religious books, which stood so upright and proud for hundreds of years, it would seem to me, that these were not books at all, but rather great spirits, living people standing before me. And I would converse with them, with living and immortal beings such as these.”

Greetings -- I’ve been given 15 minutes to speak about the Strashun Library, which operated for more than 40 years. Just as one could summarize the 40 years the Israelites wandered in the desert with two words: “Matan Torah” [The Giving of the Torah], so I will too characterize the Strashun Library with two words: “Mikdash Me’at” [The Temple]. For this is the same way in which its chief librarian, Khaykl Lunski, regarded the library: “This is the temple, in which I was educated and witnessed the happiness of my life… sometimes, when I would pass amongst the bookshelves and glance at the religious books, which stood so upright and proud for hundreds of years, it would seem to me, that these were not books at all, but rather great spirits, living people standing before me. And I would converse with them, with living and immortal beings such as these.”

At last, we are speaking here on the topic of body and soul, and more precisely put -- of matter and spirit. Many nations and peoples built empires, magnificent material edifices, built chiefly with human blood, whereas the Jewish people were completely focused on building an empire of spirit, grounded in morality. And the Jewish people have not ceased in building this spiritual empire and they will continue to do so as long as they live. This is the only empire, which cannot

collapse, be ruined, annihilated, or cease to exist. These intellectual treasures of the Jewish people have not only found their home in the Strashun Library in Vilna, but they have also inspired many people to dedicate their lives to its research, as well as for the writing of their own work; and, by doing so, they have made their own contributions to the inexhaustible intellectual treasures of the Jewish people.

The wealthy, private library of Matisyahu Strashun (1817 - 1885) served as the basis for the library. Matisyahu Strashun was considered a genius. He was called a walking library. As a thirteen year old boy, he married the eldest daughter of the magnet Yosef Eliyahu Elishberg and from that point on he became very affluent. His affluence enabled him to build an impressive rare book collection. In this connection, his house served throughout the course of his life as a center of maskilim [Jewish enlightenment thinkers]. Due to the fact that two of his sons died in their youth, he designated Jewish Vilna in his will as the recipient of his library. The library was moved to a building, which was custom made for it, and officially opened under its roof on October 20th, 1902.

Matisyahu Strashun’s private collection consisted of around 5,750 religious and non-religious books, as well as Hebrew manuscripts. Their bibliographical contents were printed in the catalogue Lekutei Shoshanim (Berlin, 1889). Among them were five incunabula, as well as approximately 300 books from the 16th century. Throughout the years, many of the book collections of researchers, writers, and intellectuals were added to the library. By 1940, the library’s collections amounted to 50,000 books. Amongst the estimated 30,000 catalogued books, 13,000 were in Hebrew (except those that were described in Lekutei Shoshanim), and 5,478 books were in Yiddish. In fact, the Strashun Library was the biggest national Jewish library in the world and its net worth was appraised by the best bibliophiles to be around three

million dollars.

The Strashun Library was essentially an accessible institution of religious and scholarly literature, which was open to the public throughout the week, closed only on the Sabbath

afternoon. In its reading room, both men and women, religious and secular, young and old, religious students and university students alike studied side-by-side beside two long tables. The silence, which permeated the library, was never disturbed by debates or disputes amongst the readers, who represented a wide-spectrum of political opinions, worldviews, and lifestyles. In various periods, the number of visitors to the library fluctuated. For example, in 1925, close to 300 readers came to the library every day and approximately 100,000 came in the entire year.

The director of the library was Yitskhak Strashun, a relative of Matisyahu Strashun; and besides him, Khaykl Lunski (1881 - 1943), who worked in the library since he was 14 years old and right until its closing in 1941.

Lunski displayed the utmost professionalism in all aspects of the library -- from building, organizing, selecting, administering over and preserving its collections, to providing the readers with help and with bibliographical consultations. His depth of personality, command of the

Hebrew language, and terrific expertise in the library’s collections enabled him to help the reader locate whatever materials one desired. Besides being a librarian, who was well-liked by the visitors of the library, he was also a writer, a journalist, a bibliographer, a book collector, and the secretary of the [Jewish] Society for History and Ethnography. Lunski, who was devoted to the Zionist ideology, worked primarily on the tasks of documentation and memorialization. His preoccupation with these tasks was reflected in both his communal involvement and in his writings (written in Hebrew and in Yiddish), such as in his book From the Vilna Ghetto [Fun vilner geto]. Further, for embodying to a large degree the spirit of the “Jerusalem of Lithuania,” he was honored with the title of the “Keeper of the Jerusalem of Lithuania.” And in spite of the fact that he lived in squalor, Lunski provided many people with help.

The Strashun Library was a source of pride for the Jews of Vilna and it was renown amongst world Jewry. Prominent people would come from all over the world to visit the library; among them were: community leaders, writers, artists, researchers, and Zionist leaders. The impression the library made on them is echoed in the “Golden Book”, i.e. in the guestbook, where they would leave comments. Thanks to Khaykl Lunski’s article on this book, as well as to the

numerous quotations he drew from it, we can track these visitors, despite the fact that the book itself vanished. For example, the Yiddish poet and playwright H. Leivik (the pen name of L. Halpern) visited the library on July 15, 1925, writing down in its pages: “What shall I write?

Silence is best; I am awe-struck.”

As I mentioned before, the Strashun Library established a name for itself and many experts spoke highly of its holdings. I will now take this moment to discuss two of these experts: the former, a doctor, who studied from 1934 to 1936 in the Institute for Jewish Studies in the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and the latter a professor of Jewish Studies. They both took an invested interest in the treasures of Jewish art and culture, and they both assumed a pivotal role within Hitler’s special initiative, aimed solely at looting these treasures from all corners of occupied Europe, and in delivering them to the “Institute for Study of the Jewish Question” in Frankfurt am Main, which was headed by Alfred Rosenberg. The former was Dr. Johannes Paul, who, in being responsible for the daily operation of the institute, was sent especially by the Nazi party to study in the Hebrew University; the latter, on the other hand, was the professor for

Jewish Studies in Berlin, Dr. Gotthardt, who arrived in Vilna in the Summer of 1941 and began to gather information related to Jewish collections in museums, libraries, and synagogues. When the Nazis commandeered the library, its director Yitskhok Strashun hung himself by his tefillin

strap.

We owe a great debt of gratitude to many people for risking their lives to rescue the surviving remnants of the Strashun Library’s prized possessions, including: the agents of the “Paper Brigade” and the director of the Book Palace of Lithuania, Dr. Antanas Ulpis, as well as Lucy Davidowitz, who found books from the Strashun Library in the warehouses of Offenbach in Germany, where millions of Judaica were stored after the war. These items were found in the “Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question” and Davidowitz worked in transferring them to the YIVO Institute in New York.

I want to especially praise the YIVO Institute for its stubbornness in not only preserving these books, but in giving them a future! I consider the Vilna Collections Project a resurrection of the Strashun Library in that it is a kind of declaration that the library will once again be open.

Thanks to this project, the surviving remnants of this library will be accessible once more, drawing in people from all over the world, aiding them in their research and in the writing of

their books. And, by doing so, it will contribute to the inexhaustible intellectual treasures of the Jewish people. I thank the YIVO Institute with my whole heart for the opportunity afforded me to present to you the history of the Strashun Library, where I see above all a history of the

triumph of spirit over matter, of the soul over the body!

And I will conclude with these words, which were jointly written in the “Golden Book” by the author Moshe Shalit and the activist Dr. Shmuel Vays:

“Today on the tenth of May, 1933, under the ringing of music, Jewish books are being burnt in the bonfires of fanatic fools! Go to Vilna to the synagogue courtyards! You can burn everything; for you can break our bodies, but never the Jewish spirit.”

From: The Story of a Library which was the Cultural Center of the Jews of Vilna / Nathan Cohen – Ha’aretz 7.4.2013.

Despite Mattitiyahu Shtrashun’s firm opposition to the Hibat Zion Movement, which was made up of Vilna Zionists, it was actually they who carried out his Will regarding his library. Thanks to their initiative, a new, spacious building was inaugurated adjacent to the Great Synagogue (1902). In accordance with the conditions set by the authorities for opening the library, it was determined that books written in Polish may not be included in the library (to prevent Jews from identifying with the national aspiration of the Polish minority in the Russian Empire, a minority that had already provoked the wrath of the authorities).

The long-term funding of the library was never guaranteed, certainly not generous assistance. The library’s administrative board frequently had to approach various sources for assistance regarding its material existence, and find ways to continue operating even when it seemed that they had run out of resources. Using a number of archival sources, the research author, Freda Schor, details a series of crises the library had undergone and highlights the difficulties of operating it even in seemingly better times.

The library was open to the public on weekdays from 11.00 – 15.00 and from 18.00 – 22.00. It was open on Friday mornings and on Shabbat during the afternoon hours (without desecrating the Shabbat). In 1904, a lending library was opened, operating separately from the main library (from which one could not take books without specific authorization). Borrowing books from the lending library was open to everybody in return for a one-time deposit of 50₽ (Kopeks) and a monthly guarantee of 10₽ per book.

Other than the first printed catalog of Rabbi Mattitiyahu Shtrashun’s estate, Likutey Shoshanim (A Gathering of Roses Berlin, 1908), no updated catalog was published by the library during the decades of its existence. Although records and cataloging were undertaken, none ever came to fruition. The library’s collection grew thanks to the many donations and bequests from intellectuals who saw it as a living foundation for the spiritual treasures of the people of Israel. According to official statistics, there were about 25,000 books in the library in 1928, approximately 35,000 in 1935 and, on the eve of WWII the number had risen to about 45,000.

As with other spiritual treasures in Eastern Europe, the end of the Shtrashun Library came with the Soviet takeover of Vilna at the outbreak of World War II. As part of the dismantling of the community and its institutions, the Shtrashun Library was handed over to the Commissar of Education, and from 1st November 1940, it was renamed "People's Library No. 4." Its contents were transferred for "kashrut" inspection and a great deal was confiscated.

With Nazi Germany gaining control over parts of the Soviet Union during Operation Barbarossa, the theft of the spiritual treasures became more extensive and violent. Yitzhak Shtrashun, who ran the library on behalf of his relative, could not endure the spiritual and material destruction and put an end to his life at the beginning of the German occupation.

Adolf Rosenberg ran the Institute for Research on the Jewish Question. Within the framework of ‘Rosenberg’s Bureau’, a group of Jewish intellectuals was appointed, headed by the librarian Herman Kruk and his deputy, the researcher and philosopher Zelig Kalmanovich, in order to sort and organize tens of thousands of books which had been confiscated from Vilna libraries and brought to YIVO – the Institute for Jewish Research, for forwarding to Germany. This group of intellectuals, nicknamed The Paper Brigade was, for all intents and purposes, an underground cell and risked their lives by spiriting away and hiding thousands of books and tens of thousands of documents between March 1942 and September 1943, at the end of which month the Vilna Ghetto was liquidated. At the same time, the YIVO library continued to function as a library, serving its readership and acting as a meeting place for members of the ghetto’s clandestine fighters.

After the war, the remains of the Shtrashun Library, and other libraries, were found scattered in various places, many in imminent danger of obliteration. Thanks to the determination and hard work of Abraham Sutzkever, Shmerke Kaczerginski, Lucy Dawidowicz, and the directors of YIVO in New York, tens of thousands of books and documents were saved from extinction, including a large part of the contents of the Shtrashun Library.