The Children's Home in Vilna

The Children's Home in Vilna/ by Leah Kessel

Zvia Wildshtein was the director of the orphanage in the Vilna Ghetto that was located in the synagogue at 10 Strashun Street. She had been a teacher before the outbreak of war. Later she was taken to Ponary but managed to evade the shooting, escape and return to the ghetto. After the fall of the ghetto, when the girls at the orphanage were annihilated, she fled from Vilna and found a hiding place with a Lithuanian family in the vicinity of Niemenczyn. When the war ended, she returned to Vilna and saw Jewish children roaming the streets and groveling for food in the trash cans. She assembled the children, found food for them and put them up in one of the houses that had been abandoned during the war. Once it became evident that the house was too small for all the children, she turned to several Jewish leaders who had been partisans or found refuge in the forest – Avraham Sutzkever, Abba Kovner and Shmaryahu Kaczerginski – and asked them to apply to the Municipality of Vilna to give them some land and a permit to build a Jewish orphanage. They received the permit after they had explained that the Jewish children had suffered greatly during the war and were in need of a place where they would receive special treatment and rehabilitation facilities. After a while she realized that there were Jewish children in monasteries and churches; there were also Jewish orphans who had been left with Lithuanian families who were unwilling to part with them or wanted a ransom in return for the release of the children.

Zvia Wildshtein was the director of the orphanage in the Vilna Ghetto that was located in the synagogue at 10 Strashun Street. She had been a teacher before the outbreak of war. Later she was taken to Ponary but managed to evade the shooting, escape and return to the ghetto. After the fall of the ghetto, when the girls at the orphanage were annihilated, she fled from Vilna and found a hiding place with a Lithuanian family in the vicinity of Niemenczyn. When the war ended, she returned to Vilna and saw Jewish children roaming the streets and groveling for food in the trash cans. She assembled the children, found food for them and put them up in one of the houses that had been abandoned during the war. Once it became evident that the house was too small for all the children, she turned to several Jewish leaders who had been partisans or found refuge in the forest – Avraham Sutzkever, Abba Kovner and Shmaryahu Kaczerginski – and asked them to apply to the Municipality of Vilna to give them some land and a permit to build a Jewish orphanage. They received the permit after they had explained that the Jewish children had suffered greatly during the war and were in need of a place where they would receive special treatment and rehabilitation facilities. After a while she realized that there were Jewish children in monasteries and churches; there were also Jewish orphans who had been left with Lithuanian families who were unwilling to part with them or wanted a ransom in return for the release of the children.

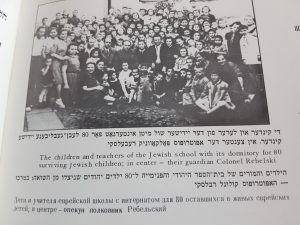

Zvia was assisted by Professor Josef Rebelski, a psychiatrist who was a high-ranking officer in the Red Army, and director of a mental asylum for Red Army soldiers. Wearing his army uniform, he joined her in her search; in this way they managed to get children out of the monasteries and away from the Lithuanian families. He told Zvia that during the war he had picked up unfortunate children along the wayside and taken care of them. He offered his help to Zvia Wildstein's Jewish orphanage. As a Jew, he believed that the future of the Jewish children was of paramount importance.

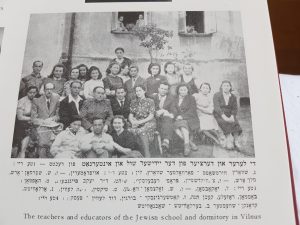

When Professor Rebelski and Zvia decided to cooperate, they were joined by Dr.Benjamin Bludz who was the manager of the Sick Funds of the families of the Red Army. Word of the Jewish orphanage spread and more children came to the orphanage. 13-14 year-olds who had hidden in the forests with the partisans also came. Some of them became counselors and even taught the younger children. It was difficult to find teachers to teach at the orphanage because those who had survived were employed by the Communist authorities doing other work. Eventually, they managed to find a few teachers such as Zlata Kaczerginski, Shulamit Wolpe, Tehila Tiktin and David Yellin, all of whom went on to teach in Israel.

With the help of Professor Rebelski they were given a small building that had been a Talmud Torah (a primary school that concentrated on Jewish Studies) before the war, however, after a short time they were asked to vacate the building in favor of a Lithuanian school. Professor Rebelski located a derelict four-storey building which had been ransacked; it had no windows or doors and the roof was broken. Rebelski brought some of his patients who renovated the building, cleaned it up and turned it into a dormitory and school. Zvia Wildstein was shocked when she saw the mental patients doing the renovations because she was afraid that the authorities would discover what Rebelski was doing. However, he reassured her, saying: "They are not mental patients. They are extremely intelligent but they do not want to be sent to the front to fight. I keep their secret and they keep mine." The pupils and teachers, with the help of the "renovators" collected bits of furniture that they found on the streets and in the abandoned houses for the orphanage. Everything that Professor Rebelski obtained for them was from the German loot that the Red Army found: beds, blankets, military clothing items (including German-army warm jackets that the children had worn during the cold winters), cases of drugs, writing implements and notebooks. Once several cows arrived on a train and they were put to graze in a field not far from the orphanage; the cows were milked daily and the children received fresh milk until one morning, it was discovered that the cows had been stolen.

Jews from all over and even from other countries heard about the orphanage and began sending a variety of parcels for the children. There were even "celebrities", such as the well-known Yiddish actor Mikhoels, the writer Bergelson, Peretz Markish and others, who paid a visit to the orphanage.

Adjacent to the orphanage's dormitory there was a school which was attended by the children from the orphanage as well as by children who were living with their families. Even some of the members of the Association of Jews from Vilna and Vicinity in Israel, attended the school such as Aharon Einat and Daniel Schmookler. The ages of the children at the school ranged from kindergarteners to high school leavers. The language of instruction was Yiddish. They had sport, theater and dance groups. The school's reputation spread far and wide. The most emotional scenes were when a parent who had survived the inferno arrived and found his missing child there at the orphanage.

Eliezer Yerushalmi, the school principal, helped the children put out a weekly newsletter. At one stage a group of orphans from Tashkent arrived at the orphanage; their principal was a fanatic Jewish communist named Shohat. He was appointed principal by the communist authorities when Zvia Wildstein was appointed deputy-head. Almost immediately, the language of instruction was changed to Russian and the Jewish characteristics slowly disappeared.

In 1949 the communist Municipality of Vilna decided that there was no longer any need for a Jewish orphanage. The children's home was closed down and the younger children were transferred to mixed orphanages of Jewish and Lithuanian children; the older children were sent to vocational schools or other schools that catered to their abilities.

In 2010, a reunion was held at Beit Vilna for the alumni of Children's Home No. 6 and Jewish School No. 9 in Vilna.