Abraham Sutzkever

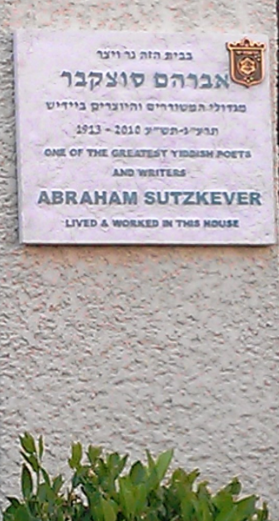

Abraham Sutzkever (Yiddish: אַבֿרהם סוצקעווער — Avrom Sutskever; Hebrew: אברהם סוצקבר; July 15, 1913 – January 20, 2010) was an acclaimed Yiddish poet. The New York Times wrote that Sutzkever was "the greatest poet of the Holocaust."

Abraham Sutzkever (Yiddish: אַבֿרהם סוצקעווער — Avrom Sutskever; Hebrew: אברהם סוצקבר; July 15, 1913 – January 20, 2010) was an acclaimed Yiddish poet. The New York Times wrote that Sutzkever was "the greatest poet of the Holocaust."

Abraham (Avrom) Sutzkever was born on July 15, 1913, in Smorgon, Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire, now Smarhon’, Belarus. During World War I, his family moved to Omsk, Siberia, where his father, Hertz Sutzkever, died. In 1921, his mother, Rayne (née Fainberg), moved the family to Vilnius, where Sutzkever attended cheder.

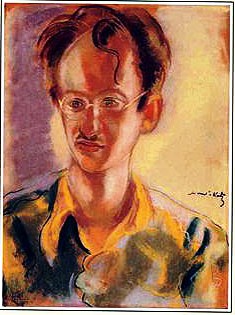

Sutzkever attended the Polish Jewish high school Herzliah, audited university classes in Polish literature, and was introduced by a friend to Russian poetry. His earliest poems were written in Hebrew.

In 1930 Sutzkever joined the Jewish scouting organization, Bin ("Bee"), in whose magazine he published his first piece. There he also met with wife Freydke. In 1933, he became part of the writers’ and artists’ group Yung-Vilne, along with fellow poets Shmerke Kaczerginski, Chaim Grade, and Leyzer Volf.

He married Freydke in 1939, a day before the start of World War II.

In 1941, following the Nazi occupation of Vilnius, Sutzkever and his wife were sent to the Vilna Ghetto. Sutzkever and his friends hid a diary by Theodor Herzl, drawings by Marc Chagall and Alexander Bogen, and other treasured works behind plaster and brick walls in the ghetto. His mother and newborn son were murdered by the Nazis. On September 12, 1943, he and his wife escaped to the forests, and together with fellow Yiddish poet Shmerke Kaczerginski, he fought the occupying forces as a partisan. Sutzkever joined a Jewish unit and was smuggled into the Soviet Union.

Sutzkever's 1943 narrative poem, Kol Nidre, reached the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in Moscow, whose members included Ilya Ehrenburg and Solomon Mikhoels, as well as the exiled future president of Soviet Lithuania, Justas Paleckis. They implored the Kremlin to rescue him. So an aircraft located Sutzkever and Freydke in March 1944, and flew them to Moscow, where their daughter, Rina, was born.

In February 1946, he was called up as a witness at the Nuremberg trials, testifying against Franz Murer, the murderer of his mother and son. After a brief sojourn in Poland and Paris, he emigrated to Mandatory Palestine, arriving in Tel Aviv in 1947.

In 1947, his family arrived in Tel Aviv. Within two years Sutzkever founded Di Goldene Keyt (The Golden Chain)".

Sutzkever was a keen traveller, touring South American jungles and African savannahs, where the sight of elephants and the song of a Basotho chief inspired more Yiddish verse.

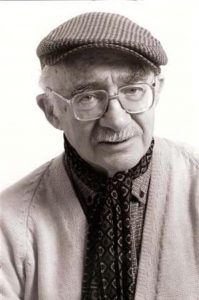

Belatedly, in 1985 Sutzkever became the first Yiddish writer to win the prestigious Israel Prize for his literature. An English compendium appeared in 1991.

Freydke died in 2003. Rina and another daughter, Mira, survive him, along with two grandchildren.

Abraham Sutzkever died on January 20, 2010, in Tel Aviv at the age of 96.

Sutzkever wrote poetry from an early age, initially in Hebrew. He published his first poem in Bin, the Jewish scouts magazine. Sutzkever was among the Modernist writers and artists of the Yung Vilne ("Young Vilna") group in the early 1930s. In 1937, his first volume of Yiddish poetry, Lider (Songs), was published by the Yiddish PEN International Club; a second, Valdiks (Of the Forest; 1940), appeared after he moved from Warsaw, during the interval of Lithuanian autonomy.

In Moscow, he wrote a chronicle of his experiences in the Vilna ghetto (Fun vilner geto,1946), a poetry collection Lider fun geto (1946; “Songs from the Ghetto”) and began Geheymshtot ("Secret City",1948), an epic poem about Jews hiding in the sewers of Vilna.

Works

- Di festung (1945; “The Fortress”)

- About a Herring (1946)

- Yidishe gas (1948; “Jewish Street”)

- Sibir (1953; "Siberia")

- In midber Sinai (1957; "In the Sinai Desert")

- Di fidlroyz (1974; "The Fiddle Rose: Poems 1970–1972")

- Griner akvaryum (1975; “Green Aquarium”)

- Fun alte un yunge ksav-yadn (1982; "Laughter Beneath the Forest: Poems from Old and New Manuscripts")

In 1949, Sutzkever founded the yiddish literary quarterly Di goldene keyt (The Golden Chain), Israel's only Yiddish literary quarterly, which he edited until its demise in 1995. Sutzkever resuscitated the careers of Yiddish writers from Europe, the Americas, the Soviet Union and Israel. Official Zionism, however, dismissed Yiddish as a defeatist diaspora argot. "They will not uproot my tongue," he retorted. "I shall wake all generations with my roar."

Sutzkever's poetry was translated into Hebrew by Nathan Alterman, Avraham Shlonsky and Leah Goldberg. In the 1930s, his work was translated into Russian by Boris Pasternak.

Works in English translation

- Siberia: A Poem, translated by Jacob Sonntag in 1961, part of the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works.

- Burnt Pearls : Ghetto Poems of Abraham Sutzkever, translated from the Yiddish by Seymour Mayne; introduction by Ruth R. Wisse. Oakville, Ont.: Mosaic Press, 1981. ISBN 0-88962-142-X

- The Fiddle Rose: Poems, 1970-1972, Abraham Sutzkever; selected and translated by Ruth Whitman; drawings by Marc Chagall; introduction by Ruth R. Wisse. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8143-2001-5

- A. Sutzkever: Selected Poetry and Prose, translated from the Yiddish by Barbara and Benjamin Harshav; with an introduction by Benjamin Harshav. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0-520-06539-5

- Laughter Beneath the Forest : Poems from Old and Recent Manuscripts by Abraham Sutzkever; translated from the Yiddish by Barnett Zumoff; with an introductory essay by Emanuel S. Goldsmith. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0-88125-555-6

Awards and recognition

- In 1969, Surzkever was awarded the Itzik Manger Prize for Yiddish literature.

- In 1985, Sutzkever was awarded the Israel Prize for Yiddish literature. Sutkever's poems have been translated into 30 languages.

Recordings

- Hilda Bronstein, A Vogn Shikh, lyrics by Avrom Sutzkever, music by Tomas Novotny Yiddish Songs Old and New, ARC Records

- Karsten Troyke, Leg den Kopf auf meine Knie, lyrics by Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger, Itzik Manger and Abraham Sutzkever, music by Karsten Troyke

- Abraham Sutzkever, The Poetry of Abraham Sutzkever (Vilno Poet): Read in Yiddish, produced by Ruth Wise on Folkways Records

Compositions

- "The Twin-Sisters" - "Der Tsvilingl", music by Daniel Galay, text by Avrum Sutzkever. Narrator (Yiddish) Michael Ben-Avraham, The Israeli String Quartet for Contemporary Music (Violin, Viola, Cello), percussion, piano. First performance: Tel-Aviv 2/10/2003 on the 90th birthday of Avrum Sutzkever.

- "The Seed of Dream", music by Lori Laitman, based on poems by Abraham Sutzkever as translated by C.K. Williams and Leonard Wolf. Commissioned by The Music of Remembrance organization in Seattle. First performed in May 2005 at Benaroya Hall in Seattle by baritone Erich Parce, pianist Mina Miller, and cellist Amos Yang. Recent performance on January 28, 2008, by the Chamber Music Society of Southwest Florida by mezzo-soprano Janelle McCoy, cellist Adam Satinsky and pianist Bella Gutshtein of the Russian Music Salon.

- Sutzkever's poem "Poezye" was set to music by composer Alex Weiser as a part of his song cycle "and all the days were purple."

From: Wikipedia

Read Ruth Wisse article in Commentary The Last Great Yiddish Poet?

Under Your white stars (Translated by Eliyahu Mishulovin)

Under Your white stars

Stretch to me Your white hand.

My words are tears,

That want to rest in Your hand.

See, their spark dims

Through my penetrating cellar eyes.

And I don’t have a corner from which

To return them to You.

And yet I still want, dear God,

To confide in You all that I possess,

For in me rages a fire

And in the fire—my days.

But in cellars and in holes

The murderous quiet weeps.

I run higher, over rooftops

And I search: Where are You, where?

Something strange pursues me

Across stairs and yards with lament.

I hang—a ruptured string,

And I sing to You:

Under Your white stars

Stretch to me Your white hand.

My words are tears,

That want to rest in Your hand.

Eulogy by Michael Schemyavitz, Chairman of the Association of Jews from Vilna and the Vicinity in Israel

Wrapped in grief and sorrow, we mourn the death of the great Yiddish poet Avraham Sutzkever, who passed away on January 20, 2010.

Sutzkever was born in the town of Smorgon in the Vilna district, in 1913. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Lithuanian Jews were deported to Siberia, including the Sutzkever family.

At the end of the war, the family returned to Vilna.

From the age of 13, Avraham Sutzkever wrote poetry, first in Hebrew and then in Yiddish. The well-known Yung Vilne (Young Vilna) literary circle accepted him as a member. His talent stood out from the beginning.

After the German invasion of Vilna and the establishment of the ghetto, Sutzkever worked with dedication and danger to save rare books from the YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research) collection. He joined the Vilna Ghetto underground. He risked his life more than once smuggling arms into the ghetto.

Even under the harsh conditions of the ghetto, Sutzkever wrote poems that from every line the pain of murdered Jews cried out. Fear and trembling grip the reader when reading "Kol Nidre," "Today is Yahrzeit, " and "Under Your White Star."

With his friends of the underground, Sutzkever succeeded to reach the partisans in the Narocz forests area. When it became known in the Soviet Union that he was in the partisan camp, they sent a plane to bring him to Moscow, where he joined the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) - a body established by the Soviet government whose members included Jewish writers, artists and scientists.

At the Nuremberg trials held after the end of the war, when the top echelons of the Nazi regime were tried, Sutzkever appeared as a witness and told the Allied judges of the horrors of the murder of the Jewish people.

Sutzkever immigrated to Israel in 1947, and founded the prestigious Yiddish literary journal, Di goldene keyt (The Golden Chain). He has won dozens of literary prizes, including the Israel Prize. The Tel Aviv City Council awarded him the title of "Yakir Tel Aviv" (Honored Citizen of Tel Aviv) in an impressive ceremony attended by dozens of members of our Association.

At a rally marking the 50th anniversary of the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto in 1993, Sutzkever read his essay "Heint is Jahrzeit,"(Today is the Anniversary of a Death).

The Association of Jews from Vilna and Vicinity in Israel, bows its head, and in sorrow and pain accompanies a spiritual giant, the greatest of his generation, a Vilna man, poet of the bloody period. May his Memory be Blessed.

From Vilna with love: The life of a remarkable Yiddish poet Mati Shemoelof , October 20, 2018

The documentary Black Honey, The Life and Poetry of Abraham Sutzkever, which screens this month as part of the Jewish International Film Festival, tells not only the story of the greatest Yiddish poet of the 20th century, it also shows the greatness of Yiddish culture before the Holocaust.

A copy of his book of poems, Kol Nidre, found its way into the hands of the Soviet Union’s leaders, who were so touched by the first poetic testimony of the mass murder of the Nazis that he wanted to meet the young Jewish poet. In what sounds like a Hollywood script, the regime sent two planes to take Sutzkever from the woods near Vilna. The first plane was shot down by the Nazis and a second one arrived two weeks later. In February 1946, he was called up as a witness at the Nuremberg trials, testifying against Franz Murer, the murderer of his mother and son.

Israeli actress Hadas Kalderon is the grand-daughter of Sutzkever and is part of the Beit Lesin Theatre in Israel. Her family connection meant that Kalderon was both a screenwriter and a co-producer in the documentary. She brings personal insights to the subject. “My grandfather didn’t want to do a documentary while he was alive. He was really serious about making his poetry work. He never engaged with the “side effects” (interviews or documentaries) of his mission to keep the Yiddish culture alive after the Holocaust. Sutzkever even turned down the famous French director Claude Lanzmann (who made Shoah) when he wanted to interview to him.

How did you come to make a film about him?

I had started to film his story, by myself, back in the 1990s. And when he died in 2010, aged 96, and hardly anyone showed up at his funeral in Israel, I decided to make a film. Ten years ago I was in a TV series directed by Uri Barbash, and I gave him a poetry book of my grandfather’s. I told him that one day we will make a film out about him. Uri was the first person who believed in the idea, and the rest is history – Barbash directed Black Honey (the film was co-produced by Yair Qedar).

How was it to grow up as the grand-daughter of Sutzkever?

I was very influenced by the story of his life, both in my life and in my art. He told me many stories from the war but only good or heroic stories. For instance, like how he was rescued with my grandmother. Then one time, I went to Europe to an antique store, in Czechoslovakia. I saw a yellow badge, the Star of David that Jews were forced to wear, and I wanted to buy it. The clerk said it would cost US$200. I told my grandfather I didn’t buy it because of the price. He said to me with a little smile: “That is very interesting because I got it for free.”

The movie tells a beautiful story about how he wrote a poem every day.

Sutzkever believed that he was saved because of his poetry. “My Yiddish and my poetry are stronger than any German bullets. Even in the ghetto with my poetry I am a free man because I have something that is a miracle, that is more beautiful than anything else – and that is my poetry.”

We also learn how, while still in the ghetto, he was leader of the “Paper Brigade”.

The Germans wanted to make a museum of Jewish culture after the Jewish people will cease to exist. They had in mind, not only the genocide of the people but also the genocide of our culture. In the Vilna Ghetto, a group of Jewish poets and scholars were chosen by the Nazis to be slave librarians.

While other Jews were trying to smuggle food in, they smuggled in rare, important books like Herzl’s diary, and drawings by Marc Chagall. They hid them in walls, caves, basements, etc. Sutzkever rescued books that now live in New York, Vilna and Jerusalem. In that way, he rescued the human spirit.

In 1949, when he immigrated from Moscow to Israel, the young state forbade public Yiddish performances. How did he respond?

My grandfather said that if he wasn’t afraid from the Goy (the non-Jew), he wouldn’t be afraid from the Jewish people. In 1956 Sutzkever wrote his first long poem, called In Midbar Sinai (In Sinai desert) and sent it to Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, who said was a great poem. ”But why did you write it in Yiddish and not in Hebrew?” Sutzkever send him back his answer, with a poem named Yiddish, which is about what would have happened if you try to take the Yiddish tongue out of his mouth, my skin.

“So come and try, if you succeed to do it, I will swallow it and then I will:

“…Open my mouth,

and like a lion

Garbed in fiery scarlet,

I shall swallow the language as it sets.

and wake all the generation with my roar!”

(Translated by: Yiddish book centre)

Obviously, Sutzkever had a strong spirit. Do you feel it is still alive?

The making of the movie paralleled the life of Sutzkever. It was a long and winding road with a lot of closed doors. At first the documentary was rejected by the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation and we asked a crowd funding platform for 145,000 NIS ($A56,000) and we got 150,625 NIS – the biggest amount ever raised for a movie in Israel. The audience became involved in the making of the movie. And in that way. Something like a Jewish social change (“Tikkun”) occurred toward Sutzkever’s poetry and towards Yiddish culture in general’.