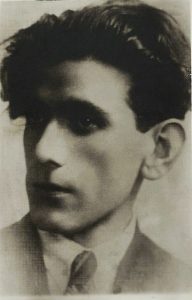

Moshe Kulbak

(1896–1937), Yiddish poet, novelist, and dramatist. Born in Smorgon near Vilna, Moyshe Kulbak was educated in a modern heder, in a Jewish Russian elementary school, and later in yeshivas. As a result, he acquired a deeper understanding of traditional Jewish culture than had most of his subsequent contemporaries in Yiddish poetry. During World War I, he lived in Kovno, where he began to write Hebrew poetry. He made his Yiddish debut in 1916 with a poem that was set to music and that became popular.

(1896–1937), Yiddish poet, novelist, and dramatist. Born in Smorgon near Vilna, Moyshe Kulbak was educated in a modern heder, in a Jewish Russian elementary school, and later in yeshivas. As a result, he acquired a deeper understanding of traditional Jewish culture than had most of his subsequent contemporaries in Yiddish poetry. During World War I, he lived in Kovno, where he began to write Hebrew poetry. He made his Yiddish debut in 1916 with a poem that was set to music and that became popular.

In 1918, Kulbak moved to Minsk, where he taught and wrote poetry. A year later he relocated to Vilna, where in 1920 he published his first book, Shirim (Poems), which confirmed his place as a poet in the Yiddish romantic tradition of Dovid Eynhorn. In the same year, Kulbak moved to Berlin in order to expand his intellectual horizons; during his three years there, he became familiar with contemporary currents in European literature, particularly with expressionism, which was to have a significant influence on his subsequent work. Kulbak contributed to Yiddish periodicals in Berlin, Poland, and especially in the New York-based Di tsukunft, where he published poems, his epic Raysn ([the Jewish term for the region of] Belorussia; 1922), and his drama Yankev Frank (Jacob Frank). In 1924, in Berlin, he published his first prose work, Meshiekh ben Efrayim.

In 1923, Kulbak returned to Vilna, where he became one of the most popular figures in Yiddish cultural life. He taught Yiddish literature in the local Yiddish high schools and in the Yiddish Teachers’ Seminary, where with his students he performed plays from the Yiddish and general repertoire. Kulbak was also a popular public speaker on literary themes and was active in Vilna’s Yiddish cultural institutions, serving, among other positions, as the chair of the newly founded Yiddish PEN Club. During this time he wrote the long poems Vilne (1926) and Bunye un Bere afn shliakh (Bunye and Bere on the Road; 1927), along with lyric poems, and his second significant novella, Montog (Monday; 1926), as well as literary articles. Following his departure from Vilna in 1928, an edition of his collected works in three volumes was published (1929), to which was later added a reprint of his novel of the Soviet period, Zelmenyaner.

Despite his students’ devotion and his popularity as a teacher, writer, and lecturer, in 1928 Kulbak moved to Minsk, where much of his family lived. The growth of Yiddish cultural institutions in the Soviet Union on the one hand, and the constricted atmosphere in Poland on the other were also central factors in his decision to move. In Minsk, Kulbak wrote the long poem Disner Tshayld-Harold (Childe Harold from Disna [a town now in Belarus]; 1933), and two dramas, Boytre (1936) and Benyomin Magidov (unpublished; now lost), but most essentially he focused on the novel Zelmenyaner, about the fate of a traditional Jewish family facing the new conditions of the Soviet Union (vol. 1, 1931; vol. 2, 1935). Kulbak also translated Russian and Belorussian literature and directed editorial projects. Only a portion of his pre-Soviet poetry was allowed to be republished in the Soviet Union, where two small collections of his verse appeared.

Kulbak’s poetry from 1916 to 1928 is characteristically romantic in tone. He places nature in its pantheistic aspects at the center of his concerns and adopts a refined yet folksy tone by intermingling elements of stylization and primitivism. Indeed, several of his poems stress modern themes and became popular with young radicals—for example, the long poem Shtot (City; 1920)—but the urban setting is mediated through the perspective of a wanderer arriving from afar. Raysn celebrates a widely extended family of simple, everyday people who spend their lives in intimate connection with nature. The language of this poem blends characteristic stylistic strains from Yiddish and Slavic folk songs together with biblical allusions, with an ironic note occasionally intruding on the poem’s idealized atmosphere. Vilne distinguishes itself with its loaded cultural references and dramatic language, which simultaneously praises the Jewish city and its rich heritage and laments its decline.

Under the circumstances in the Soviet Union, it was difficult for Kulbak to continue writing, and in his time there he almost stopped publishing lyric poetry entirely. On the other hand, in that period he wrote Disner Tshayld-Harold, in which he portrays the journey of a young intellectual from Jewish Lithuania who comes to study in the metropolis of Berlin and absorbs its particular atmosphere. This long piece is written in a mock-epic and self-reflective tone, directed both toward the experiences of the protagonist himself and toward descriptions of the wider cultural and human spectrum of the metropolis. Dynamic, colorful, and refined language is juxtaposed with a feeling of doomed decadence.

Kulbak’s prose works of the 1920s, Meshiekh ben Efrayim and Montog, signal his turn to modernism. In them, he strove to formulate in an original manner the central spiritual problems of his generation: revolution, apocalypse, and messianism. With a seemingly loose narrative structure, Meshiekh ben Efrayim ties together the most extreme opposites—redemption and death, eroticism and violence, and the complicated relationship between the masses and their leaders. The protagonist of this work is a simple Jew who lives a vegetative existence in the heart of the Slavic landscape. This character is crowned the redeemer, even though he does not believe in his messianic calling. He is consumed by an overwhelming desire for death, and in the grotesque conclusion of the work he falls victim to the same believers who had previously followed him.

Montog, subtitled “A Small Novel,” depicts the post-1917 revolutionary fervor in an unnamed Jewish town. The work is built on an ambiguous contrast between the declared tendency toward passivity in the protagonist, a Hebrew teacher and “rootless” intellectual, and the atmosphere of revolutionary activity and combativeness around him. His conduct and the existential course of his ideas call into question all the shared values associated with the quest for intellectual achievement and the conventions of materialistic bourgeois culture, as well as the clichés of revolutionary slogans. Both Montog and Meshiekh ben Efrayim conclude with the death of the protagonist, formulated as a senseless act. In both, too, the narrator creates a rich network of ironic and parodic allusions to a broad range of texts, from the New Testament to Y. L. Peretz’s Di goldene keyt.

Despite the dramatic changes in all aspects of Kulbak’s work during his Soviet period, he continued to create antiheroes, and maintained the ability to weave a faint note of humor and irony into his works. Thanks to these virtues, Zelmenyaner is one of the most significant achievements in Soviet Yiddish prose. The narrator concentrates on two generations of an extended Jewish family in Minsk, who face the profound changes brought on by the Soviet regime and its lifestyle. Taking into consideration the accepted conventions of Soviet literary policies, one would expect a sharp divide between the “negative” types of the older generation and the “positive” ones among the young, but thanks to his sense of humor the narrator creates an intricate portrait that leaves no room for simple revolutionary optimism. When publishing the second volume in 1935, Kulbak was obligated to keep in mind the requirements of Soviet criticism, but even then he was able to protect his work from too much one-sidedness.

Kulbak also attempted to distinguish himself as a dramatist. His play Boytre, about the romanticized figure of a Jewish bandit set in the nineteenth century, scored a significant theatrical success; from 1936 on it was performed in Soviet Yiddish theaters as well as in overseas fellow-traveler theatrical circles. In 1937, Benyomin Magidov was under preparation in the Birobidzhan Yiddish theater, but the manuscript has been lost.

Kulbak’s arrest in 1937 was part of the Stalinist repression that affected the Minsk Yiddish writers and cultural activists with particular vehemence. Following a perfunctory show trial, he was shot on 29 October of that year. After his death several editions of his collected works were published, none of them particularly reliable, due to the negligence of their editors (e.g., editions from New York, 1953, and Buenos Aires, 1976), or due to biased selections and editing (e.g., Gut iz der mentsh [Man Is Good]; Moscow, 1979). Translations of his work have appeared in German, Hebrew, French, English, and Russian.