Chiune Sugihara

Visas to Japan

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. Accordingly, when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, the Soviet Union occupied the country’s eastern parts. Following the Germans attack on Poland and the beginning of the persecution of the Jews there, many fled eastwards. Some 15,000 Jews from Poland arrived in the still independent Lithuania. Caught between the Nazis and the Soviets, they were desperately seeking ways to emigrate. When the Soviets occupied Lithuania in 1940, the Jews’ plight intensified.

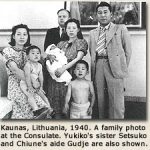

In November 1939, Chiune-Sempo Sugihara, a Japanese career diplomat, was sent to Kovno (Kaunas), then the capital of Lithuania, to serve as Japan's Consul. As part of his job, he was to monitor the maneuvers of the German Army across the border, so that Japanese headquarters would know in advance of the anticipated German attack on the Soviet Union.

When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940, all foreign diplomats were asked to leave Kovno by the end of August. As he was packing his belongings, Sugihara was informed that a Jewish delegation was waiting in front of his consulate, asking to see him. The delegation was headed by Zerach Warhaftig – a Jewish refugee who was to become years later a minister in the government of the State of Israel. Sugihara agreed to meet with the delegation for a brief conversation. The Jewish delegation had come with a desperate request.

The Jewish refugees in Lithuania were in dire straits, watching as the gates to the world were closed to them. It had become practically impossible to obtain immigration visas to anywhere in the world. In their desperate search for countries that would permit them to enter, they had found out that Curacao – a Dutch colony – required no entry visas. This would enable them to leave Lithuania, but since the war had blocked all travel possibilities westwards, the delegation had come to the Japanese Consul with the request to issue transit visas. With these transit visas they would be able to obtain permission to cross the Soviet Union.

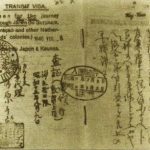

The Japanese consul asked for time to obtain authorization from his superiors to grant the visas. Nothing indicated that the Japanese Foreign Ministry would agree to this unusual request. However, Sugihara was very troubled by the refugees' plight and therefore began issuing visas at his own initiative and without having obtained his ministry’s support. Nine days later, the response from Tokyo arrived. The ministry rejected any change in the instructions and reiterated that the conditions for issuing transit visas were the existence of a valid visa for the applicant's final destination and proof that the applicant would be able to pay the travel to their final destination and for their stay in Japan. Although many of the Jews did not fall within these criteria, Sugihara decided to continue with the distribution of the visas anyhow. His wife later described how the predicament of the desperate Jewish refugees had affected her husband. After the meeting with the delegation, he was troubled and contemplative until he decided to go ahead and disobey his orders. Within a brief span of time before the consulate was closed down and Sugihara had to leave Kaunas, he provided between 2,100 and 3,500 transit visas. Thanks to Sugihara they were able to leave Europe and the murder that was to begin a year later. Among the recipients of visas were many rabbis and Talmudic students. Their narrow escape enabled them to re-establish the Jewish traditional schools elsewhere.

With a near deadline for leaving the country and a small staff, Sugihara stamped some of the passports himself. It is said that he was stamping passports even at the railway station, as he was leaving Lithuania. He also enlisted the help of some of the Jews to stamp the passports. With no knowledge of Japanese, some of the stamps were put in upside down. While all this was going on, Sugihara was receiving dispatches from Tokyo warning him against issuing visas without due process.

Over fifty years later, Sugihara's wife, Yukiko, described those days in an Interview to the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation: "At the beginning there were about 200 maybe 300 people. They stood there from morning till night, waiting for an answer. They also stood like this the following day and the day after. They stood all the time. And their small children together with them. People who had escaped from Poland, a place dangerous for them, and together with their children walking day and night, reached Kaunas and the Japanese Consulate asking for visas. They had risked their lives in order to reach this place, their bodies exhausted, their clothes torn and their faces tired. I would see them from my window, when they saw me looking at them, they would put their hands together (as if praying). It was so hard for me to watch these scenes… they were so miserable. Two days passed, and my husband sent another telegram, for the third time. The answer was the same answer, no matter how many telegrams: do not issue visas. We did not know what to do….We could not sleep at night. We kept thinking and thinking what to do. In addition to that, I had a baby, we had three young children. If my husband issues the visas contrary to the Foreign Office instructions, then when we return to Japan, my husband would for sure lose his job … We were thinking and thinking what to do, and the representatives of the refugees begged and begged ”please give us the visas".

From Kaunas Sugihara was sent to open a consulate in Koenigsberg (today Kaliningrad) and then to Bucharest. Upon his return to his country in 1946 Sugihara was dismissed from the Japanese Foreign Service. His understanding was that this was a consequence of his insubordination as consul in Kaunas. From then on he had to make a living doing odd jobs.

The visas granted by Sugihara saved the Jews from the Holocaust. When Nazi Germany invaded Lithuania in June 1941, the small window of escape was slammed shut. The killing of the Jews began immediately after occupation, and the majority of the Jews in the occupied territories were murdered.

On October 4, 1984, Yad Vashem recognized Chiune-Sempo Sugihara as Righteous Among the Nations.

Tamar Ravitz was born in Warsaw, Poland; she was a member of the Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair and when war broke out in 1939, she fled on the same train as the members of the Polish government to Rivne and the surrounding villages. When the Soviets arrived, she moved to Vilna with her parents and her father managed to get an exit visa, with the help of a friend, from the Japanese consul, Chiune Sugihara. At the end of 1940, the family traveled to Japan where they stayed for about two months and got visas to America, within the framework of visas that were issued to intellectual refugees. In 1941 they moved to America and ten years later they came to Israel.

I only know a little about the story of the Japanese consul Sugihara but I do not know anything about what went on in the interim. A few years ago I became more curious about how we managed to get the visa to Japan so I went to talk to Mordechai Tsanin who went to Japan together with us, then came to Israel and was the editor of Letste Nayes (Latest News). He then told me things that I had not known about how we got the visa to Japan. I had known that that my father was in Kovno and, one day, he came home and said to my mother: "We have a visa to Japan."

Q: Just a minute, what was in Kovno? Did he go specially to get it?

A: They were always traveling back and forth from Vilna to Kovno because the consulates were in Kovno, so the only way to get out of Vilna was to go to Kovno. I think I can still remember that when he came home, my mother burst into tears. For her, Japan was the end of the world.

Q: But it wasn't really a visa; it was a transit pass.

A: No, it was an entry visa – a tourist visa, a temporary visa.

Q: That's it. It was supposed to be temporary.

A: Yes, but you could leave with that visa.

Q: But when your father came and said: "We have a visa for Japan, did he then describe the route you would be taking?"

A: There was no route, you got on the train and travelled east.

Q: No, there was a point. In other words, the visa was issued and those transit passes were given to Japan so that Jews could get to the island of Curacao that was under Dutch rule, which, to me, sounds even worse than Japan.

A: We were given a visa to Japan. There was no other visa.

Q: Right, because you did not need a visa to enter Curacao and the whole point was to finally get to the island.

A: I think that their aim was somehow to get to Palestine or the U.S.A., but first of all, you had to get out.

Q: I would imagine that there were problems getting the visa because those who were active in getting visas were the Mizrahi movement and religious groups and not people like my father.

A: I don't know but I can tell you my father's story as I heard it from Tsanin. Tsanin was a member of the Bund, but, for personal reasons, he very much wanted to go to Palestine. He was friendly with my father, who said: "Do you know what? I am going to talk to the association of journalists about you; perhaps when the certificates arrive, there will also be one for you." They went and father began to praise Tsanin. However, Tsanin noticed that there was something amiss and after he left, they said to father: Moses, what are you talking about? He is a loyal Bundist, why did you bring him? Why should he get a certificate? Tsanin understood that this was not going to work. They were staying together at the same hotel, maybe even sharing a room. According to Tsanin, he turned to father and said: "Mendel, why are you so worried?" father answered: "I have a wife and two children. I have to get out of here." Tsanin also wanted to leave very much; he wanted to get to Palestine for personal reasons. He was so desperate that that same evening he went to the Japanese Consulate after closing time.

Q: What do you mean he went? Weren't there long lines of people waiting?

A: I can only tell you what he told me. I don't know if it was before or after but it could not have been after because there was no after. Perhaps it was before there was a massive onslaught of requests. By the time he got there the gate was closed but Mordechai Tsanin was very charismatic and the guard was Polish. He spoke to him in Polish, charmed him in Polish and the guard let him in. He went into the house, spoke to Sugihara and burst into tears. That was what he told me. I wasn't there. Sugihara asked him: "What happened to you?" Tsanin answered: "I must get out of here, my life is in danger, I really must get out." Sugihara responded: "Fine, wait outside. At that moment he saw father walking in the street. He said: "It was a basement and I saw his legs. He said to father: "Mendel, Mendel, give me your passport." My father handed him the passport through the window and he stamped the visa in my father's passport too. That was how we got the visa to Japan. It was sheer chance who survived, who was saved and who managed to flee. It was maybe 5% brainpower and 95% luck. It was sheer chance. So we had a visa to Japan but we still had to get an exit permit from the U.S.S.R.

The Story of One of the Greatest Righteous Among the Nations /by Ya'arit Glazer

Seventy-eight years ago, on July 15, 1940, Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara, Japan's Vice-Consul in Kovno, Lithuania's capital, began issuing entry visas to Jewish Holocaust refugees. When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union, the Soviet authorities intended to move all foreign consular representatives from Kovno. The Japanese consulate was also to be closed. There were many Jewish refugees in Kovno trapped there waiting to flee to Europe. The world's gates were locked, and it was impossible to pass through the Soviet Union without a valid visa to a final destination. However, it was learned that the island of Curaçao in the Caribbean, which was under the auspices of the Netherlands, did not require entry visas. The Soviets gave their consent for refugees to move through the Soviet Union on their way to Curaçao, provided they received transit visas from Japan. Consequently, Dr. Zerach Warhaftig, one of the leaders of the Mizrahi, turned to Vice-Consul Sugihara and asked for the visas.

Although his government rejected the request, Sugihara decided to act and grant visas to Jewish refugees lining the doors of the consulate. In the remaining weeks before his departure from Kovno, scheduled for August 31, he devoted most of his time to issuing these visas. Many yeshiva students, such as Mir Yeshiva students who also fled to Lithuania, took the opportunity to leave. They eventually reached China, where they stayed during the war years, and from there to the United States and Israel. At least 1,600 visas were issued (according to Sugihara's estimate, the number reached close to 3,500).

On his return to Tokyo in 1947, after being appointed head of other European missions, Sugihara was asked to resign from the diplomatic service because of his refusal to obey government instructions seven years earlier.

In 1984, Yad Vashem recognized him as the Righteous Among the Nations.

I am in touch with his son who is much involved with the commemoration of his righteous father.

Memorial plaque was unveiled in honor of Chiune Sugihara in Jerusalem

Justice Minister visits city where 'Japanese Schindler' saved thousands of Jews.

The story of the Japanese city of Tsuruga, where thousands of Jews were rescued from certain death, has been under the radar for decades. By Joy Bernard November 13, 2017

Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked visits Japanese city of Tsugura where thousands of Jews were saved during the Holocaust.

Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked became on Sunday the first Israeli minister to visit Tsuruga, a city in Japan’s Fukui Prefecture where 6,000 Jews were rescued during the Holocaust by Japanese government official Chiune Sugihara.

Sugihara has since been dubbed the “Japanese Schindler.”

Shaked is on an official visit to Japan and is expected to conduct professional meetings with the heads of Japan’s justice system as well as hold lectures for Japanese students about the challenges the State of Israel faces.

The city of Tsuruga opened its gates and its heart to 6,000 Jews who escaped the reach of the Nazi regime during the Holocaust.

Shaked visited the city’s museum, which commemorates the rescue actions that were undertaken to aid the Jews in flight.

Many of them were students of the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Mir Yeshiva, having arrived in Japan with visas that were made for them by then-Japanese vice consul in Lithuania, Sugihara, who acted against the stance of the Japanese government.

Sugihara was awarded the title of ‘Righteous Among the Nations’ by Yad Vashem and is the only Japanese person to have ever been honored as such.

During her visit, Shaked officially thanked the people of Tsuruga on behalf of the Israeli government and people for saving Jewish lives in their city. “We will never forget Chiune Sugihara and the generosity of the residents of Tsuruga,” Shaked said in a press conference.

“They didn’t hesitate to open their homes and their hearts to 6,000 Jewish refugees who escaped the Nazis. The city of Tsuruga and its residents are role models for the young generation in Japan, who are learning about our joint responsibility to act with determination against hatred and violence and to stand up to racism, xenophobia and persecutions of any people, whoever they may be,” she stressed.

Tsuruga’s Mayor Takanobu Fuchikami told Shaked that he is currently working to better commemorate the Holocaust and the rescue of Jews in the city.

Fuchikami said that he also intends on making Tsuruga an attractive tourism destination for Israelis, adding that Shaked’s visit will help reach those goals.

The justice minister told the mayor that she intends to ask Education Minister Naftali Bennett to emphasize the activity of righteous gentiles worldwide into the school syllabus, including the moving story of Sugihara.

The unsung heroism of Sugihara did not end with in his brave decision to issue visas to thousands of Jews at risk. He was fired from the Japanese Foreign Office for his actions and did menial labor to support his family until his death in 1986 – a year after Israel named him ‘Righteous Among the Nations.’