Bagurskas

The Potato-Sack Siblings

Four young families lived in one apartment in the ghetto, the Broyeris, Dvoretz, Muller and Kaltinovsky families. They were all tailors by profession, so it was probably not by chance that they went to live together. Four children, one from each family, survived. They were nicknamed by one of the parents, 'the potato-sack siblings'.

Four young families lived in one apartment in the ghetto, the Broyeris, Dvoretz, Muller and Kaltinovsky families. They were all tailors by profession, so it was probably not by chance that they went to live together. Four children, one from each family, survived. They were nicknamed by one of the parents, 'the potato-sack siblings'.

I was born on 1 January 1941. My mother, Reizel Ring, was from Pabrade, a small town near the border with Poland, where her parents owned a small shop. Their relations with their Polish neighbours were friendly and peaceful.

My father, Sleime Broyeris, was born in Shauliai. My parents met and married in Kaunas, where both worked as tailors; they were not poor but lived modestly. Father believed in communist ideas, although he was not officially a member of the Communist Party; he was imprisoned for a short time in Lithuania for his political activities. In prison he learned the Russian language; he liked to read and was strongly influenced by Soviet literature. He named his eldest son Ilya, after Ilya Erhenburg and named me Maxim, after Maxim Gorky.

Ilya spent the summer of 1941 in Pabrade with our grandparents, Leiser and Beila. In the very first days of the war, the Polish neighbours of my grandparents came to their house in search of money and jewels. They probably found nothing, so they set the house on fire. My grandparents and Ilya were burnt alive. My parents tried to escape to Russia, but because of the severe bombardment were forced to return to Kaunas.

In the ghetto we lived in a small house together with several other families. My parents told me that I would regularly go to the Dvoretz's room because they always had food. Father worked at the airfield in Aleksotas and my mother in a stocking factory called 'Silva'. She met a woman there who was willing to take a Jewish boy. She did not ask for money or goods but made one condition: the boy should not be circumcised. The guard at the fence was bribed and I, then a 3-year-old boy, was smuggled out of the ghetto in a sack of potatoes. As agreed, somebody picked me up and carried me to my rescuers, the Bagurskas family.

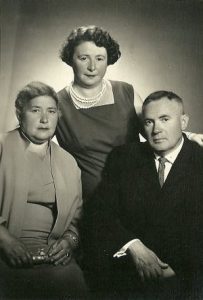

The Bagurskas lived in a village called Mikalinava where they had a farm and owned a small shop. Juozapas and Marijona Bagurskas had three children of their own: two daughters, Danute and Aldute, and a son, Vytautas, who was handicapped. I was treated well in this family, exactly as the other children were. I spoke mainly Yiddish, but soon I began to forget Yiddish and speak Lithuanian. Nevertheless I was kept hidden from strangers' eyes. I was baptized and named Albinas Bagurskas. I called Mr Bagurskas by his first name, Juozapas but, when I spoke to his wife I called her 'Pone', (Mrs) Bagurskiene.

I remember several episodes from this period. All the family used to pray at certain hours. I was not forced to pray, but I remember Mrs Bagurskiene saying to me, 'Always tell the truth. God sees and hears everything, and whoever lies will be punished.' And I asked her, 'How can God hear us and see us from so far?'

I remember how frightened I was when I saw a German soldier sitting on the fence of the Bagurskas farm, picking apples from a tree. Vytautas and I hid together in the attic: he did not want to be sent to labour camps in Germany and I was taught to avoid any contact with other people. When the front line approached, our village suffered severe bombardment and the nearby match factory was bombed. Everybody ran to a shelter in the garden. I was left alone on the porch of the house: I was afraid to run in the darkness.

Meanwhile, my father managed to escape from the ghetto to a partisan detachment, where he fought, together with Boris Dvagovsky's father. Their brigade took part in the liberation of Kaunas from the fascists, and together with the Soviet Army entered the city in August 1944. Immediately after the liberation of Kaunas my father took me from the Bagurskas family. However, he was then mobilized to the Soviet Army with other members of the detachment. He had to place me in the Jewish orphanage where I was to spend several months. I remember that food was scarce, mainly porridge, and Mrs Bagurskiene used to visit me and bring some food. After several visits, she was asked to stop visiting me, because the other children were jealous.

I had a friend in the orphanage. Together we dug a hole in a corner behind a pile of logs, and we would hide there when somebody unfamiliar came to the orphanage. It was only when my mother returned from Stutthof that I went to live with my parents again. Our family maintained a friendly relationship with the Bagurskas family; I spent my summer holidays there and joined their children in everyday activities, looking after the cow, horse and pigs.

Pone Bagurskiene did not support the Soviet regime and used to say that Hitler and Stalin were the same thing. The Bagurskas lost almost all of their property when the Soviets returned, but fortunately were not exiled to Siberia.

Later, when both Mr and Mrs Bagurskas had passed away, I asked Aldute, their eldest daughter, 'Why did your parents rescue me, endangering all the family?' Her simple reply surprised me, 'Vytautas was disabled and a man would be needed to work the farm in the future.'

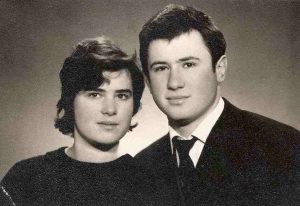

I did not experience anti-Semitism personally, maybe because I did not look like a Jew, but I heard a lot anti-Semitic expressions. My schoolmate told us proudly once that his father had tortured and killed Jews during the war. 'When I am grown up, I will kill Jews too,' he said. I graduated from Kaunas Polytechnic Institute as a machine engineer, married Salia Bichovsky, a medical doctor, and we emigrated with our first daughter to Israel in 1972, where our second daughter was born. During all the years in Israel we worked in our professions and liked what we did. Our daughters and three grandchildren all live in Israel.

I am grateful to God that I am among the saved and feel blessed to live.