Anti-Nazi Resistance

First Call for Resistance to the Nazis in the Vilna Ghetto: “Let us Not Go Like Sheep to the Slaughter” / By : Daniela Ozacky-Stern, June 2019.

On the cold night of 31 December 1941 a group of about 150 young Jews crowded in the small kitchen of Vilna Ghetto, in Straszuna Str. No.2. They pretended to be celebrating the New Year’s Eve, to distract the attention of their German and Lithuanian guards, who were in the process of getting drunk.

The meeting was in fact held in memory of the Jews who were murdered in the past months in the forest of Ponary (Paneriai in Lithuanian, located approximately 15 kilometres south-west of Vilnius), and one of the survivors who escaped from the death pits was invited to give her testimony about her experience, having narrowly escaped death.

In the course of that evening a proclamation was read in Yiddish by Abba Kovner and in Hebrew by Tosia Altman. That proclamation symbolized the initial idea of resistance which started to bloom in the minds of those youth movement members, after experiencing the mass massacre of their Jewish brothers and sisters in Lithuania. The original document, handwritten in Yiddish by Abba Kovner, is preserved in the Moreshet Archive, located in Givat Haviva, Israel, under the archival number (symbolization) D.1.4630. The document was written at the end of 1941, in a Polish Dominican monastery near Vilna. The nuns of the monastery, under the guidance of Anna Borkowska, a Polish cloistered Dominican nun, who served as the prioress of this monastery, helped sheltered Jews. In 1984 Borkowska was awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem for her rescue efforts. Kovner, who was one of the founders of Moreshet brought to the archive this unique document, in addition to other original documents from Vilna Ghetto.

The Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye (FPO), or United Partisan Organization, was formed on 21 January 1942 in the ghetto. It took for its motto "We will not go like sheep to the slaughter," proposed by Abba Kovner.This was one of the first resistance organizations established in a Nazi ghetto. Unlike in other ghettos, the resistance movement in the Vilna Ghetto was not run by ghetto officials. Jacob Gens, appointed head of the ghetto by the Nazis but originally chief of police, ostensibly cooperated with German officials in stopping armed struggle. The FPO represented the full spectrum of political persuasions and parties in Jewish life. It was led by Yitzhak Wittenberg, Josef Glazman, and Abba Kovner. The purposes of the FPO were to establish a means for the self-defence of the ghetto population, to sabotage German industrial and military activities, and to support the broader struggle of partisans and Red Army operatives against German forces. Poet Hirsh Glick, a ghetto inmate who later died after being deported to Estonia, penned the words for what became the famous Partisan Hymn, Zog nit keyn mol.

In early 1943, the Germans caught a member of the Communist underground, who, under torture, revealed some contacts; the Judenrat, in response to German threats, tried to turn Wittenberg, head of the FPO, over to the Gestapo. The Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye organized an uprising and was able to rescue him after he was seized in the apartment of Jacob Gens in a fight with Jewish ghetto police. Gens brought in heavies, the leaders of the work brigades, and effectively turned the majority of the population against the resistance members, claiming they were provoking the Germans and asking rhetorically whether it was worth sacrificing tens of thousands for the sake of one man. Ghetto prisoners assembled and demanded the FPO give Wittenberg up. Ultimately, Wittenberg himself made the decision to submit to Nazi demands. He was taken to Gestapo headquarters in Vilnius and was reportedly found dead in his cell the next morning. Most people believed he had committed suicide. The rumour was that Gens had slipped him a cyanide pill in their final meeting.

The FPO was demoralized by this chain of events and began to pursue a policy of sending young people out to the forest to join other Jewish partisans. This was controversial as well because the Germans applied a policy of "collective responsibility" under which all family members of anyone who had joined the partisans were executed. In the Vilna Ghetto, a "family" often included a non-relation who registered as a member of the family in order to receive housing and a pitiful food ration.

When the Germans came to liquidate the ghetto in September 1943, members of the FPO went on alert. Gens took control of the liquidation in order to keep the Nazi forces out of the ghetto and away from a partisan ambush, but helped fill the quota of Jews with those who could fight but were not necessarily part of the resistance. The FPO fled to the forest and fought with the partisans.

Further reading: Revenging Partisans

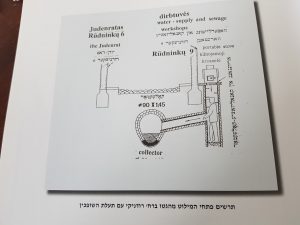

The Vilna Sewage System - Material Collected by Tzvi Schwarzman

The sewage system in Vilna, built at the end of the 19th century, was ten kilometers long and a section of it passed beneath the old city. Along its entire length the system was constructed with tunnels of different sizes with a rectangular finish and drainage pipes. Nowadays it is no longer in use; very few people know about it or are interested in it. However, during the Holocaust period the Jews in the ghetto used it efficiently to smuggle goods and weapons. On the day the ghetto was liquidated it became an escape route for some 100 people from the underground.

Tzvi Schwartzman, who participated in the “March of the Living for Vilna-Ponar” in 2009, that was organized by the Association of Jews from Vilna, made contact with a student from Lithuania by the name of Lukas Platchkes, a researcher of insects in dark places, and the two of them started to reconstruct the previous route. They began their mission in the German sewage tunnels in Vokieciu Street (in Iddish- Deutsche Gasse) in the old city. When they started the reconstruction the entrance to the tunnel was still concealed. The sewage system was still full of damp and water. Tzvika recalls: 'we had to walk bent over the whole and to keep the camera safe. Lukas Platchkes, the guide, walked quickly and I had to keep up with him. It was not easy. The tunnel kept changing shape – from a very narrow, low opening to a wide and high one. He tried opening a heavy rusty manhole cover without success. As we continued on we discovered rat holes, flowers and mushrooms and in contrast the filth that remained from the previous sewer, until we could finally see the “light at the end of the tunnel”'.

The tun nel, part of which was destroyed in Stalin’s era, was planned in a very interesting structural form and extends to all areas of the old city. The tunnel led to the former Lietuva cinema, and another part of the tunnel ended at Subaciaus Street.

nel, part of which was destroyed in Stalin’s era, was planned in a very interesting structural form and extends to all areas of the old city. The tunnel led to the former Lietuva cinema, and another part of the tunnel ended at Subaciaus Street.

Moscow newspapers today report how forty emaciated, tubercular Jews spent ten months in the sewers of Vilna to escape execution by the Germans. / Jewish telegraphic agency

The group, led by Mikhail Spokoiny and his brother, both engineers, decided in September 1943, when the Nazis began to liquidate the Vilna ghetto, that the only possibility of escaping death was to retreat to “fox holes” in the sewer system which had been prepared for temporary use during German man-hunts.

Through a man-hole within the ghetto precincts several hundred Jews descended into the sewers. Most of these kept on until they reached the outskirts of the city from whence they fled to join partisan bands. The Spokoiny group, which included several children, set up primitive house-keeping in a foxhole which had been equipped by them with electricity and running water. Food was supplied by a Polish superintendent of a building located above their hiding place He also brought German newspapers for the adults and crayons and picture books for the children.

One day the superintendent notified them that their fox hole had been discovered and that they would have to flee. From then on, Spokoiny said, things grew indescribably difficult. They were out off from all light, water and food. But from reports obtained from their Polish friend of German activity in the city’s streets, they realized that the Red Army must be approaching Vilna. They determined, therefore, to hold out as long as possible.

Crouched in the sewers they heard the noise of battle above them. At one point, Spokoiny advanced to a position where he could hear the voices of Russian soldiers, but he was unable to communicate with them. Finally, after four days of severe fighting, the Germans retreated and the sewer-dwellers emerged. As a result of inactivity, they could hardly walk, Their bodies were covered with sores. Their eyes were pained by the light, and all of them spat blood.

Escaping from the Ghetto via the Sewers – as described by Hasia Taubes, in an interview with the students at “Ulpanat Tzvia” (Tzvia High School) Herzliya

Nobody noticed how I felt, and the same went for many of us whose parents and siblings were left behind. What’s more, my closest friends were no longer alive. They were sent to Estonia with the second contingent three weeks earlier. When it was my turn to go down into the sewers, I slid in through the opening of the pipeline. There was an abyss under my legs, a black void in front of me, a sense of the unknown and losing my way. My mother was left behind, as was all my energy, which had diminished considerably by then. It didn’t take one minute for me to find myself folded up into a tunnel the diameter of which prevented me from standing up straight. My feet sank into muck that became deeper and deeper. The filth penetrated my bones, the stench was choking me and searing my eyes. This wasn’t a time for feelings, there was no turning back, more people had come down the tunnel after me, and the line crawled onwards.

I quickly got used to the situation. As I was unable to continue all bent over, all I could do was to crawl on all fours, sinking into the liquid muck that was steadily rising.

It was relatively easy for me because I was short. For my friends who were taller it was much more difficult. And it was a long way to go. The other opening of the tunnel through which we were supposed to exit was far from the entrance. Moreover, one of the group fainted and blocked the tunnel with his body. The line came to a standstill, we could neither proceed nor go back. It looked like that was the end. The apparent lack of an exit was what prompted us to drag the unconscious body of our friend and push him halfway into an adjacent tunnel where there was some meshing for rainwater as well as for air and light. The line continued forward at a snail’s pace. The young man who had fainted regained consciousness, returned to the line and continued with the little strength he had left.

This took place during the autumn. It had started to rain and we were in danger of being submerged if it began to pour. I had no control over my actions. My mind was not working, everything seemed unclear, my senses were not functioning and my movements had become involuntary. It could be that the poisonous gases in the sewer were responsible for that. Yet there still remained within me a desire to live, both for my own self and for others. I was part of a complex mass, susceptible to danger, whose destination and desire to survive drove its collective actions towards relief from all the hardships and achieving a goal.

Today I cannot assess either the length of the sewers, or the time it took for us to move through them or where we eventually emerged.

When we came out from underground dusk was falling, it was nearly dark. The fresh clean air was such a contrast and it invigorated me. My limbs over which I had had little control, slowly returned to normal and my sensations began to revive. I felt chilly, wet and moldy, my filthy stinking soaking clothes restricted my movements. I didn’t know where I was, it was somewhere in the town, silent and desolate. As we left the opening of the sewer we received instructions to quickly join up in pairs and hurry away from the place. I have no recollection of my partner on this “trip”. I didn’t know the way to our destination. We were given orders to keep eye contact between the groups. The streets were partially lit and compared to the gloom in the sewers they were somewhat blinding. A light rain began to fall and it gently touched the stinking sludge adhering to my clothes. But it wasn’t heavy enough to wash it off.

There were relatively few passers-by in the rainy evening and among them we could see German and Lithuanian soldiers. There was a definite danger that we would be noticed and suspicion would be aroused because of our clothes that looked disgusting and awful and because of the stink coming from them.

Later we found out that the path we took passed by the square where the Germans had taken the Jews they had rounded up on the day the ghetto was destroyed. They were held there until all of them were forced out and sorted: those allowed to live were sent to work in Estonia and those bound for death were sent to Ponar. Some ten thousand Jews were sorted during those three days. They were told to sit like a herd of animals out in the open, starving, with no water, in the pouring rain, freezing cold, each person fearing his fate and the fate of his family…

Life in a Partisan Unit / a chapter from the book Beyond the Clouds by Baruch Shub/Shuv, Chairman of the Israel Organization of Partisans, Underground Fighters and Ghetto Rebels.

It took a while for me to acclimatize to the unit. I was assigned a bunk at one end of the trench. The bunks were made of rough wooden boards and padded with anything soft we could lay our hands on: bits of torn blankets, worn-out clothing, bits of fur and mats, which were also used as clothing, blankets and sheets at one and the same time. During the day, the trench was empty except for a few fighters who had just returned from night activity. Most of the people preferred to stay outside. However, things changed in the evenings. Everybody would crowd inside and only the guards and officials were absent. We would only partially undress and lie down with our rifles and bullets next to our bodies with our guns and valuables at our heads. Often in the evenings, especially during the hot summer evenings, someone would light a fire, and we would sit around, relax and then someone would burst into song. We weren’t worried that the flame of the fire would give us away. Being deep in the forest, we were protected.

New additions were allocated a place to sleep at the end of the trench. The more senior they became they progressed towards the center, where there was a heater, which was where everyone got together. This is where we talked about our experiences, told jokes and drank Samogon (moonshine). Also, those in the know prepared original national dishes.

The unit was made up of diverse nationalities. There was a small number of Lithuanians, including those parachuted in, but since they were veterans and commanders, they lived in trench used as headquarters, and so there was little personal contact. Those prominent in the general fighters’ trench were the Russians, the Belarusians and the Ukrainians, with a few Uzbeks and Tartars, most of them military men, and escaped prisoners. The Poles were in the minority, local farmers who had joined us, not necessarily because they were aware of the situation but as a ‘city of refuge’: they had a rich past of theft, getting drunk and even murder. You could count the number of Jews on the fingers of both hands.

Cooking in the evening quickly became a competitive sport. Having an organized kitchen with basically a cook in charge, did not prevent the partisans from taking ingredients to cook or fry for themselves. There was no shortage of food except when those parts of the partisan forest were under siege. So, it gradually became the custom that those partisans who were not assigned to operations, would gather around the stove and taste the national dishes of whoever had done the cooking. The moonshine would loosen tongues causing provocation, for better or worse. I quickly caught on that friendships were being forged via the stomach so realized that I should join in with the cooking festivities. One evening, I said that I would prepare a Jewish Menu for the guys. I took some liver from the kitchen and started to fry it like I had so often seen it prepared at home. Never mind that it was being fried in pig fat, not exactly recommended for Jewish food, but the liver was really good which meant that I was accepted into the ‘experts’ circle, thereby promising my future as a cook. And, since there is no meal without a drink, I was, as the host, forced to raise a glass of the sharp and revolting moonshine, again and again. I tried my best not to vomit. Luckily, my mind remained clear. This ability of drinking and staying sober helped me in the following days making the goyim pretty jealous. As a result, I was royally admitted into the partisan circle.

At the beginning, I was given the job as a guard. I was temporarily attached to a platoon under the command of Juzas, a member of the Lithuanian Komsomol, from Kovno and whose civilian occupation was chimney sweep. He was one of the first to answer the call of the Communist Party and was part of the Lithuanian nucleus of the Soviet Partisan Movement. A simple goy gushing with party rhetoric, frequently drunk resulting in a loose tongue. He treated me with contempt, either because I had fallen asleep the first time I was on guard duty, or simply because I was Jewish. However, I never heard vitriolic antisemitic expressions coming out of his mouth.

I hated guard duty. Bands of partisans would go out on operations and I was left to say goodbye and wish them good luck. To start off with, I was position in the camp itself, then I was promoted and was on guard duty in the forest, and finally also the outer perimeter. I enjoyed guard duty inside the forest the most, in the middle circle where there were guards in twos and with whom it was possible to have a discussion. Since it was far from the kitchen, this guard duty was for six hours only. Friendships which were made there, continued into battle.

The guarding the outer perimeter was the most strenuous. There, in the thick and menacing forest, the guard was on his own, either sitting in a ditch or having climbed a tree, motionless, in order to discern if anyone was approaching and, if so, whether friend or foe. Since these positions were far from base, the guard shifts were changed only after six or eight hours.

Despite the physical proximity of most of the Soviet Partisan Movement and the shred living conditions, not all of them were exactly friendly. There was a marked difference between the operational bands and the administration and service personnel. The operational bands would leave the base for a number of days and needed to catch up on sleep and rest when they returned; according to the budding hierarchy they were considered the elite. The only direct, but casual contact between them and the others, was in the kitchen, the bath house and the trench (the zemlyanka). The intimacy and camaraderie between the fighters were born and existed through the operational bands. Bands competed with each other, were jealous of each other and this was expressed through flashy clothing and better food. The fighters expected their commander to take care of their needs before seeing to others, as well as giving the band a more distinguished name.

The few Jews there were not particularly close and did not even form a group. In my opinion, each one just wanted to integrate and raise his status in one or other of the units, without emphasizing his Jewish origins.

As mentioned above, Haim Lazar’s group was temporarily located at our base. In the meantime, more groups of Jews, including members of the FPO, arrived from the Narocz forest. They were all destined to join the Vilna Lithuanian Brigade which was on its way from the east, and under the command of the Jewish party member Zimonas was supposed to reorganize in the Rudniki forest. Other lone Jews, in hiding in the Rudniki forest, and not organized, also found their way to Genis. There were also rumors that there were Jews amongst those parachuted into Lithuania. No-one bothered to reveal their national identity and it would seem that they were interested in doing so either.

Additional reading:

Partisans in the Narocz Forest

Partisans in the Rudniki Forest

Following the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto, the Jewish community which had been rooted in Vilna for generations, disappeared.

A few individuals, who had been hidden by Christians, a few children hidden in churches, small groups of youths who were with the partisans and small labor camps in Vilna, were all that was left of the large Jewish community in the Jewish Vilna of days gone by.

There were two partisan headquarters in the Vilna area. One near the Narocz lake region, not far from the Glamboki forest. The second one was not far from Sorok Tatary in the Rudniki forest. At first, these were mixed groups made up of Lithuanians, Poles, White Russians and Jews under the leadership of Soviet paratroopers.

At a later stage, Jewish units were established led by Jewish fighters from the ghetto. So, in addition to the general partisan movement, there were three Jewish partisan groups in the Vilna area led by the Lithuanian Colonel Gravis. The first one went by the name ‘Death to Facism’ and was led by the ghetto fighter Abba Kovner together with Anna Borkowska. The second group went by the name ‘For Victory’ and was led by Abrashka Resel (Shabrinsky), with the third group being led on officer called Kriaklis.

There were more than 100 members in each group and were well armed with automatic weapons, grenades and machine guns. The lives of the Jewish and other partisans, was filled with danger despite their being free. The Jewish partisans were greatly respected for the way they often excelled in battle. Dozens of the heroic Jewish fighters gave up their young lives in the war against a bloodthirsty enemy. Those who died included fighters who destroyed bridges, others while laying explosives under railway tracks or while blowing up whole German convoys of cars on the highways and byways. Many Jewish partisan burial places can still be found on all the paths of the Rudniki forest. This is a testimony to the sacrifices and part of played by the Jewish fighters for victory and peace.

Throughout the whole period, there was close and constant contact between the Partisan Movement and the Jews in the Vilna camps. The partisans’ scouts would bring back regards from the Jewish fighters in the forests to those in the camps, as well as taking new people, medicines, weapons and other necessities back with them.

It is quite clear that there was no shortage of antisemitic acts from among the non-Jewish partisans. It must be said, that the partisan headquarters made great efforts to overcome the antisemitism.

At more elevated levels, the partisans lived in special earth huts surrounded by marshy swamps.

The women, who worked alongside the men, played a major role in the Jewish partisan movement.

In the middle of 1943, a pole was erected on the main road 40 km. from Vilna, with an inscription in German “Achtung! Partisan Area”. The Germans refrained from going to many of the villages for fear of the Red Partisans who had occupied the area.

On 9th July 1944, the moment the Red Army drew near to Vilna, all the partisan groups started marching in a war parade from the Rudniki forest towards the city.

Vilna was liberated on 12th July 1944. All the partisan groups, including the Jewish ones, took part in the battles to liberate the city.

During the first days following the liberation, they occupied all the important institutions in the city, as well as the police and partisan factories.

Many of the Jewish partisans were awarded the highest decoration of excellence by the Soviet government.

From: The Testimony of Dr. Moshe Feinberg

From the testimony of Chaim Lazar Litai, a member of the Jewish underground of the Vilna Ghetto, on the Ghetto Fighters House website:

The members of the underground found themselves in an embarrassing situation following Wittenberg’s extradition, and they decided to escape to the forests. Under the command of Josef Glazman, a company of the most wanted underground members, including Chaim Lazar, was formed. The night of 24th July 1943, was a sleepless night, as the fighters were busy getting organized and arming themselves. At first light, the fighters sneaked out of the Judenrat building to the ghetto gate in order to join the Jews who were leaving to go to work.

Leaving for the forest:

Once on the street, the 21 fighters formed themselves into a group of lumberjacks equipped with axes and saws. Zundel Leizersohn dressed up as a Jewish policeman and led the group. They left the ghetto and walked towards New Vileyka, about 15 km from Vilna. Fourteen youngsters, boys and girls, joined the group of fighters on their way to the Narocz forest, about 200 km from Vilna. There were now about 35 Jews in the group.

The fighters stopped to rest in the woods towards evening and were divided into two groups – one under the command of Izka Matskevich , and the other under the command of Chaim Lazar. The fighters continued walking through the stifling night. Upon reaching the river, about 1.5 km from the forest, they realized that the single bridge was only accessible from within the village. Five fighters were sent ahead to reconnoiter. Fifty meters from the bridge, fire opened up on the other members of the group from three different directions. Some of the fighters freaked out and immediately returned fire. One long hour later, the order was given to retreat, during which time contact was lost with some of the members. 13 of the group of 35 managed to reach the swamps.

Fear started to eat away at the members of the group. A scout was sent to locate the rest of the members. Shooting could be heard getting nearer, until they felt that they were being surrounded. Suddenly, Shaike, the scout, disappeared. The fighters decided not to return to the ghetto but to wait in the forest till first light. In the morning, they met two youngsters who told them about the encounter from the previous night and the hunt for the partisans. They advised them to get out of the forest.

One of the young men brought the fighters food and acted as their guide. Three members of the group decided to return to the ghetto. They were given what was left of the food and went on their way. It was later learned that they had been captured by the enemy. The guide led them into the forest where they parted ways. The fighters gave him the little money they had left and pressed on. Throughout the day, they sent scouts disguised as farmers to reconnoiter and, when night fell, the group took the route checked out by the scouts. It took them 14 instead of five days to reach their destination.

The front must not be abandoned:

On the eve of Rosh Hashana 1943, the commander came and informed the partisan company that they would be going into action the following day. Nine fighters were chosen to go, three of whom, Chaim Lazar, Shlomo Kanterovich and Tebka Halperin, were Jewish. Their mission was to go the Vilna-Grodno Road and set an ambush for the German army in order to disrupt the movement of vehicles going to the front. The idea was to destroy German vehicles together with their occupants.

Lazar and Kanterovich were assigned the heavy machine gun, and Halperin was assigned to the light machine gun crew. They set off at dawn, set up the ambush in the bushes which lined the road, and waited for a signal from the operation commander.

The sound of cars coming from Grodno could be heard drawing near. The signal was given. The fighters opened fire on the vehicles. Only a few gun shots were heard. Some of the weapons did not work. Shouts could be heard from the German trucks carrying soldiers, but they stopped a long way from the ambush. Contrary to the partisan fighting principle, according to which no action format can be repeated in the same place, the commander decided to set up another ambush in the same bushes. About an hour later, cars could be heard coming, this time from the direction of Vilna. The fighters opened fire, but this time the Germans returned heavy fire.

Lazar and Kanterovich felt that they were alone. Looking around, they saw that their comrades in arms were running to the forest in panic. Angry with the cowardly partisans, Lazar and Kanterovich stepped up their fire on the Germans, who retaliated in force. Eventually, they had no option but to retreat. Kanterovich caught up with the rest of the force, but Lazar lagged behind as he was carrying the heavy machine gun. He came across Halperin who was also laden with ammunition. The Germans started pursuing the partisans, gradually closing in on them. Realizing that they could not continue running with their loads, Halperin and Lazar decided to hide until the Germans had passed them by. A few hours later, the sound of gunfire had subsided. Hunger was gnawing at them, and they decided to wait in their hiding place until dark.

In the meantime, the rest of the fighters had reached the partisan camp with neither clothes nor weapons. There was a great deal of embarrassment. They were upset about the two missing fighters and the lost machine gun. During the night, the camp guard discerned two people approaching. The partisans were at the ready. When the guard approached the two figures, he saw that it was Lazar and Halperin.

After their return to camp, a roll call was held. The commander rebuked the fighters who had abandoned the fight and praised the two Jewish fighters who had risked their lives and not abandoned their weapons. From that day on, the esteem of the Jews in the partisan camp rose. The following day, it was learned that three officers and 15 German soldiers had been killed in the operation.

Freedom Day in the Lithuanian forests:

Pesach (Passover) 1944. Rumors abounded for a few days about planes carrying arms coming from Moscow. On the night of the second day of Pesach the fighters went to wait for the planes which had been delayed en route. At midnight, many of the fighters returned to camp; the fire beacons had died down, and even the commanders seemed to have given up hope of the airplanes arriving. Suddenly, there was a distant sound of aircraft engines, which got louder and louder. Everyone was gripped by anticipation. The fires were rekindled. The planes flew low around the fires and dropped large packages. At dawn, the partisans roamed the forest collecting the packages. By lunchtime, a rumor had begun to spread around the camp: new weapons were being distributed to the fighters!

That same night, an ambush was set up on the Vilna-Grodno road. A few hours later, a convoy of heavy German vehicles passed by and was ambushed. The fighters opened fire on the convoy and, once they had recovered from the shock, the Germans returned fire. The fighters were close to retreating when they noticed that one of the armored vehicles was on fire. They mustered up courage and attacked the convoy. The Germans retreated in panic.

At dusk, the fighters gathered around a bonfire and gave vent to their feelings of elation by singing at the top of their voices. Suddenly, there was dead silence. One of the senior members of the group started to speak: “Today is Pesach. We haven’t changed the order of things or eaten matza. But I doubt whether, somewhere in the whole wide world, there are any other Jews who have fulfilled the festival’s mitzvot (commandments) as we have done”.