The Lithuanian 16th Division

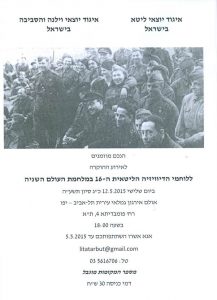

On the 12th of May, 2015 a tribute to the Jewish fighters of the 16th Lithuanian division, also marking the 70th anniversary of the victory over the Nazis, was held in Tel Aviv. The evening was produced jointly by the Association of Jews of Vilna and vicinity in Israel and the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel, with the support of the Center of Organizations of Survivors of the Holocaust.

A group of fighters of the 16th division participated in the event and a few hundred relatives and close friends were also present. The event was honored by the presence of: the Lithuanian ambassador to Israel and the cultural attaché to the Lithuanian embassy. The Lithuanian ambassador spoke to the audience in Lithuanian, Hebrew and English and then read a goodwill message from the President of Lithuania.

The fighters recalled memories, a short movie about the lives of the fighters of the division in Israel was shown, a war song sung by Nehama Lifshitz was accompanied by a video clip and Moshe Belcharovitz and Uri Abramowitz sang war songs in Russian and Yiddish, mostly because they were the languages in which the fighters of the division communicated. Excerpts from Monya Tzatskes The Flag Bearer, a book by Efraim Sevela were read. Efraim Sevela, a Lithuanian Jewish writer, director, journalist and script writer was born in Babruysk. At the age of 16 he fought in World War Two, reached Berlin and was given an award for bravery. In Vilna, after the war, he wrote one of his most famous books, Monia Tzetzkes The Flag Bearer, a work of laughter and tears telling of the life in the 16th division during World War Two. The descriptions are true-to-life but, unfortunately, we will never know where he got his information from.

The climax of the evening was the exhibition that paid tribute to the fighters of the division, the atmosphere and the way of life of the large concentration of Jewish soldiers in the division together with no fewer Russians and Lithuanians. When they marched together or sat by the campfires they lit to try and keep themselves warm in the freezing weather, they sang Hebrew and Yiddish songs that most of them had learnt at school or in youth movements. Over a third of the soldiers in the division were Jews from Lithuania who shared a Jewish cultural and national tradition. They always had the prerogative and the Jewish soldiers demonstrated it publicly. The Jewish fighters were mainly young, Hebrew-speaking, members of Zionist youth movements, members of Jewish student unions and the like.

Written by Rosa Lita'i Ben Zvi

Letters from December, 1941 to March, 1943

Elisheva and Alexander Cohen-Tzedek

Solomon Cantzdikes (Cohen-Tzedek) was known as Sergei in the underground. He was born in 1919, studied at the Hebrew high school Švabės in Kovno and was a Lithuanian revolutionary. From 1940 -1941 he was the secretary of the Komsomol in Vilna. From 1942-1945 he was a private and then an officer in the 16th Lithuanian division. In February, 1943 he was critically wounded in the battle near Alekseyevka but returned to the front after nine months in hospital. He remained in the army after the war and retired at the rank of colonel. He immigrated to Israel in 1990. He died in 2001 and was buried in Rehovot.

His wife was the renowned journalist Elisheva Cohen-Tzedek, the daughter of Ya'akov Fineberg from Vilna.

3/2/1943

My love,

Yesterday I received your letter from the 21/01. What a pity it was so short. It is such a long time since I received any detailed letter and I miss them so much! I can well understand what you are going through. After all, it has been a year since we last saw one another. It is a long time especially in our lives. We have only lived together for one and a half years. I can well appreciate what longing and loneliness are. There is no harder feeling than that. If anyone asked me what was the most difficult thing I have experienced in my life, I would say, without hesitation, loneliness.

Life has taught me to be patient so I wait despite the fact that I want to see you so much that my heart aches.

Enough talking about that. When our paths cross once more, you will feel implicitly what is impossible to express in words. I was pleased to read what you wrote about Alik. I am sure that, in spite of the many ailments and difficulties, he is big, strong, clever and talented. They say that healthy bright children are the fruit of deep love. Apparently that is so. What does science have to say about it? Psychology? It is seemingly more complex. In a few months it will be spring and Alik will start running around. Take him to the park and he can run around on the grass and have fun. This year the spring will be especially good. It will bring victories on the battlefields and they will warm our hearts as much as the spring. I have asked you a number of times to send some photos. Please try. I can't wait to see them. Today they informed us that there was an outright victory in Stalingrad. I thought about Bella (Elisheva Cohen-Tzedek's sister, a doctor who was awarded a Red Star decoration for her work during the battle of Stalingrad). She was in Stalingrad. Where is she now? My dear Shvinka, I would like to write more but I must stop now.

With warmest kisses, my darling love.

Sergei

4/03/1943

Shalom Sheva!

I haven't written any letters for a while. On the 26/02 I was wounded in the left hip from shrapnel. It is not a dangerous wound but needs time to heal. I will write more regularly from there. I haven't had any letters from you for a while (about a month) but I hope I will have at the hospital. How are you coping? How is Alik? What's news by you? I had one postcard from Bella.

Be well, my darlings.

Sergei

Two days before the end of the war

7/05/1945

I received your two letters from the 27/4 and the 28/4, my darling wife Sheva,

I can feel just how difficult it has become for you lately and I also feel that the last few days have become unbearable. We have been separated for three years, three years of hard times, loneliness, occasional sleepless nights and some joyless days. All those years you have been my beloved beautiful wife, young and fair. I have wanted so much to be with you, to hear your soft, loving voice and to hug you so hard that I hear your bones crack, to look at your warm smiling face and to rejoice in my happiness, my darling Shvinka. I want nothing more than to bring up my son proudly and happily.

Instead of that, there were journeys, wanderings, battles, attacks under showers of lead, being wounded, pain, hospital, operations, and the hardest part of it all, living without you – impossible, unbearable, Sheva! There were moments when I thought my nerves could no longer take it. I never thought of easing the pain by indulging in another relationship. Anyway, it wouldn’t help. You still don’t know what you mean to me. You are everything – I have no life without you.

I am lying down now, unable to sleep and, as usual, I will stay awake until the morning. And in the morning, as I do every day, I will go to the front line of fighters without anyone suspecting that the calm, pedantic officer who has faced death dozens of time, can hardly contain the tears when he thinks about his beloved. I am crude and even inflexible. I have buried dozens of my best friends during this war without even shedding a tear. I can bear anything but I cannot live without you. Without you I have no life.

Sheva, it has become difficult. I lit a cigarette and went out of the trench where we are hiding. Darkness! It is a dark night. The night light is from flying rockets, grenades and bullets. One can guess the distance to the front lines. The front is not quiet; neither the officer nor the soldiers can sleep. The Germans are 80 - 100 kilometers away and trying to take captives. The slightest mistake can cost lives. The war is merciless. Cruel. They shoot relentlessly. The worried Germans shoot missiles all the time. A tank has just left, shooting straight at my trench. They are asking to be attacked and they will get it. There is no reason to hold back, we must liquidate them now. I believe that it will end in the next few weeks. It will be soon. Shvinka, my darling, the love of my life, my treasure.

Yours and only yours,

Sergei

From the website of Gideon Rafael Ben-Michael / The 16th Lithuanian (Jewish) Division

In World War Two, 500,000 Jews served in the Red Army of whom 200,000 fell and 160,772 were awarded citations of merit. The 16th Lithuanian Division operated within the framework of the Red Army; however, many people are unaware of the amazing story of this division.

I wrote this article because I thought it fitting that both youngsters and older people should learn about the battles and bravery of the Jews in the Red Army during the Holocaust.

Towards the end of 1941, it was decided by the Supreme Command of the armed forces, headed by Stalin, to set up a division and to recruit to its ranks refugees from Lithuania who were dispersed across the country, senior citizens from Lithuania, and to join them up with the Lithuanian fighters from the 29th Lithuanian territorial corps, who had retreated together with the Red Army.

It was one of the rare cases when an army division was identified by its nationality. The division was established on purely political grounds, to show the world the solidarity and identification of the Lithuanian nation, as an integral part of the Soviet nation, in the latter's battle against Nazi Germany. The establishment of the division was part of a long-term plan to strengthen the Soviet Union's hold over the Baltic republics after the war. The Latvian division and the Estonian corps were established for the same reasons.

The Jewish refugees from Lithuania, particularly the younger ones, were pleased to hear about the Lithuanian division and masses of them expressed their wish to enlist in the ranks of the Red Army to join the armed struggle against Nazi Germany.

The 16th infantry division of the Red Army which, at its peak, numbered 12,000 fighters was made up of a few Lithuanians, many Russians and masses of Jews who had managed to escape from Lithuania in 1941, following the Nazi invasion. At its peak, over 50% of the members of the division were Jews; in other words, they were the largest national brigade in the division, both relatively and absolutely.

The new recruits, who arrived at the beginning of 1942 to the recruitment center in the township of Balachna, felt that this was "a Jewish division in every way". That is what they called it for quite some time until the heavy battles at the Oriol front in 1943, where masses of Jewish soldiers were killed.

Professor Dov Levin writes that one of the outstanding characteristics of the division was the very widespread use of Yiddish as the lingua franca of the Jewish soldiers; they spoke it openly without any qualms, unlike what happened, for example, in the Polish army and other armies.

In the Lithuanian division, they spoke mama loshen (Yiddish for 'mother tongue') during periods of calm as well as in combat. The soldiers sang the marches in Yiddish conducted by Leibl Wadshaw, the teacher, as they marched around Balachna and Tula.

It was in Yiddish that their officer, Moshe Bodnovski, led the attack on the Oriol front. It was also in this language that Menashe, the coachman, urged his horses on as they brought bombs to the front line. It was also in Yiddish that the soldiers encouraged one another in the heat of battle, with sayings such as "for our fathers and mothers" and more than once, the cries of Shema Yisrael (Hear O Israel, said just prior to death by Jews) and the like from the wounded at the front, could be heard.

It was a vibrant reality with spontaneous outbursts of folk singing in Yiddish and Hebrew, dancing the hora (a popular Israeli folk dance) and prayer services.

Popular folklore from the daily lives of the army soon developed. For example, before the soldiers went to the front, a few expressions entered their lexicon, such as man git a teitel (they are giving out rifles) and man teilet tachrichim (referring to the handing out of white camouflage suits in snowy conditions).

So it came about that army orders were often also transferred (especially at the lower echelons) in Yiddish. After all, both the person who gave the order and the one who received it were either: from the same town, from the same class or members of the same youth movement and they were used to conversing with one another in Yiddish before they were recruited into the army. It is no surprise that the more Yiddish that was spoken was a definite hallmark of the degree of involvement and popularity of any officer among his soldiers. It was a definite sign of identification between Jews: amcha (your people), and even between sub-units it was possible to pick up hidden "codes", such as galilah (north), negba (south) etc.

This was a unique phenomenon in the Red Army and, perhaps, in other armies as well. For example, as the time approached to move towards the front, hundreds of Jewish soldiers were called to a special assembly where there were Jewish speakers who gave Jewish recitations. When the Allied Forces were asked to open a second front and it became necessary to appeal to the public, the management of the division began a publicity campaign to encourage letter writing in any language (including Yiddish and Hebrew) to all the allied countries (including Eretz-Israel) in order to raise awareness of the need for the second front among relatives and friends. Naturally, this order was carried out willingly, because the letter writing also served a secondary purpose: searching for relatives and passing on information about the fate of Jews on both sides.

Thanks to that, communication with Israel also increased. The letters and packages that came from there containing matza, calendars and other supplies, also had a symbolic value and were widely acknowledged by all the Jewish soldiers. Postage stamps with Hebrew writing on them aroused great excitement.

The Jewish soldiers in the Lithuanian division held important positions in combat. It transpired that the young men and women from the Lithuanian cities and towns, in addition to fostering the Jewish national spirit, also proved their mettle effectively in the various fields of combat (as officers, instructors, combat engineers and the medical corps); above all, their real acts of bravery were motivated by feelings of revenge! The fact that of the one hundred and fifty Jews in the Red Army who were awarded the Soviet Union Medal of Valor, five were from the Lithuanian division speaks for itself. They were: Commander of the division, Major Leonid Buber, Private Boris Tzindal and Private Second-Class Hirsh Uzhpolis,, Sergeant First-Class Kalman Shor (who immigrated to Israel in 1979) and last, but not least, then Major, later Colonel Wolf Vilenski who succeeded in immigrating to Israel after being refused for eleven years.

A type of internal "public opinion" among the fighters developed over time which encouraged the fighting from a purely Jewish point of view. In fact, in their very first combat experience, the Jews (students, pupils, shop assistants and former yeshiva students) surprised their superiors and what a wonder it was: "During the training sessions I couldn't get the Jews to stand up," the commander of the 167th brigade said, after a blistering battle, "yet during the battle, I couldn't get them to lie down. They stormed the enemy proudly and pursued them fearlessly."

It is not surprising, therefore, that in the village of Alexeevka in the Oriol area, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of graves of Jewish soldiers who fell there during the battles; no fewer, perhaps, also fell as the Red Army advanced westward to Belorussia, Lithuania, and Kurlandia, but only a very few survived until the 8th of May, 1945, VE-Day.

Avraham Krechmer, a major in the 16th division, writes in his memoir:

The Lithuanian division was a unique phenomenon among the Jewish resistance movements against Nazi Germany for two reasons: the fact that there were almost five thousand Jewish soldiers in one combat battalion and also because of the duration of its active service, from the end of 1942 until the very last day of the war on the 8th of May, 1945.

Formally, it was the Lithuanian division of the Red Army, but, in fact, many of its fighters – soldiers and officers at all ranks—were Jewish.

We fought under a foreign flag and on foreign soil, but it was obvious to one and all that this was our war –the war of the Jews. The slogan "kill the German" complemented the feelings that beat in the hearts of the Jewish fighters of the division. Most of the fighters in the division were young, aged 18-30: Hebrew speakers, members of Zionist youth movements, members of Zionist student unions, all graduates of the illustrious educational network in Lithuania and the vicinity.

Hatred for the Nazi murderers coupled with the strong desire to avenge the blood of their parents and siblings, as well as the profound nationalistic, deep-rooted awareness were the basis for the fertile ground that produced mass acts of bravery and courage. That was a rare and unique phenomenon.

At that time, pre-IDF (Israel Defense Forces), thousands of Jewish fighters in combat units of the infantry, field cannons, anti-aircraft cannons, the engineering corps, the medical corps etc. under the command of Jewish brigade commanders, battalion commanders, company commanders, platoon commanders and squad commanders participated in bitter, bloody battles for a full two and a half years, repelled hundreds of enemy attacks, stormed enemy posts, defeated them and drove them to the shores of the Baltic Sea and eastern Prussia.

The combat trail of the Lithuanian division began in the bitter battles of the winter of 1943 (February-March) on the snowy plains of Oriol. The division participated in the well-known battles of the summer of 1943 (July) on the Oriol-Kursk "arc", successfully repelled enemy attacks, then took the offensive and liberated large areas in the direction of Oriol-Briansk, in the central front. From the fall of 1943 to the spring of 1944, the division fought difficult battles in the swamps and forests of Belarus, in the Vitebsk-Polock sector. The division continued its combat trail on Lithuanian soil, participating in battles at the entrance to Šiaulia with a resounding breakthrough via the Zemaitya region, along the Neman river to the German border and the port of Klaipeda, on the shore of the Baltic Sea.

The division completed its combat trail in the region of Tokomas-Libava in Kurlandia in Latvia where the German army was surrounded. The Germans were forced to lay down their arms at the feet of thousands of Jewish soldiers from the Lithuanian division.

Along the entire combat trail of the Lithuanian division there are mass graves and single graves of Jewish fighters, including one enormous mass grave that was dug in the frozen ground of the Russian village of Aleksejevka in the Oriol region.

Almost all of the Jewish fighters in the Lithuanian division who survived immigrated to Israel: a few came through the 'escape" routes and the illegal immigration, some as "repatriates" to Poland but the majority came at the beginning of the 70's when the gates were opened for immigration to Israel from the Soviet Union.

The fighters were awarded medals for outstanding service on the battlefield which were awarded to them by the State of Israel. This was formal recognition that the battle of the Jewish fighters in the Red Army against the Nazis was an integral part of the Jewish nation's persistent struggle to establish a sovereign Jewish state in the Land of Israel. The high concentration of Jewish fighters in the various units of the division left an indelible impression on the Jewish nature of the atmosphere and daily life of the fighters. The fighters spoke Yiddish among themselves and also with their Jewish officers. It was not uncommon for the soldiers to have Yiddish, and sometimes, Hebrew, song evenings. On the long, back-breaking treks they sang Yiddish folksongs. Occasionally, when a member of the Jewish politruk was not around, the former members of the youth movements, would softly sing Hebrew songs – Beyom Kayitz, Yom Ham (On a summer's day, on a hot day) by Bialik, Sahki, Sahki al Hahalomot (Play, play on the dreams) by Tchernikovski and the like. On Jewish festivals and holidays, especially, on the High Holy Days, the religious fighters would organize minyanim (quorums of 10 necessary for Jewish communal prayers) and hold prayer services (there was no need for prayer books because the liturgists knew the prayers by heart). On rare occasions, when one of the fighters would receive a package from Israel, all of them shared in the excitement. Soap wrappings, sweets or empty cigarette boxes were passed from hand to hand like a mascot. The fighters discussed current affairs, told anecdotes spiced with the sharp Lithuanian humor and even developed original army slang. The officers and fighters maintained a friendly relationship. Many of them were close: the officers and those under his command came from the same place, learnt together in the same class or were members of the same youth movement.

Lev Shemesh writes in his memoir: Until the 17th of October, the Germans relentlessly continued striking our positions, adding tanks and aircrafts to their attack but we repelled them successfully. Eventually, after a heavy battle, Brigade 167 captured Pelkino. I remember distinctly two acts of bravery: Shlomo Warpol, a soldier from the second battalion, was very badly wounded nevertheless he did not remove his finger from the trigger until Pelkino was taken, after which he agreed to be evacuated. In the same brigade, the head of one of the platoons, the commander of the platoon, Sargent Gelez, with his soldiers, broke through to the enemy's front line. When Gelez fell suddenly, wounded in the back, the soldiers were so fear-stricken that they lay down on the frozen ground. With his last ounce of strength, with a hoarse voice, Gelez gave the order "onward death to the Germans", stood up and, heading the platoon, burst into the enemy trenches. Here, too, there was no lack of acts of bravery. Three soldiers, the scout Yoffe, Kantor the medic and a Lithuanian sergeant whose name I cannot recall, continued storming ahead not realizing that the other soldiers had stopped. When the Germans noticed them and tried to catch them alive, Yoffe shouted: "We will fight to the last bullet which we will leave for ourselves; the enemy will not take us alive!" Kantor and the sergeant crawled back to their unit while Yoffe covered for them with his rifle. The sergeant was injured. Yoffe ordered Kantor to shower the enemy with long bursts of fire while he carried the wounded sergeant on his back to his trench. The three of them were awarded decorations of merit. Sergeant-Major Lazar Milner, who was a soldier in the enemy home front, rescued and removed wounded soldiers from the battlefield. He was rewarded with a decoration for "bravery".

Zvi Turgel writes in his memoir:

I return to the trench and check my walkie-talkie when suddenly I hear Haim Glazer shouting at me: "Grisha, there's a letter for you, I think it may be from home." I drop the phone and hurry to read the letter; my hands are trembling, perspiration covers my face, I recognize the handwriting of my sister, who was then in Uzbekistan, and I cannot believe my eyes. Am I dreaming?

As I read the first line, the letter fell from my hand: "My dear brother, our beloved mother was murdered in June, 1942 by the bestial Nazis." I want to cry but I cannot. I am petrified, I hold on to my friends who are here with me; they had anxiously awaited good news from home and, perhaps, news of their own families.

The campaign has begun and as I lie in the trench I can think of only one thing: how to avenge my mother's death and take revenge for the others who are languishing from hunger in the German detention camps. We can hear loud explosions from the tanks and other armaments. The enemy is not just hanging around. They respond with a shower of bullets and bombs exploding around us resonate strongly.

Our cannons fire incessantly. Every now and again we hear our commander give orders to fire. I shout from the trench, because my connection with the infantry platoon has been disconnected and our signal operator, Gershonas, left two hours ago and has not yet returned. I yell from the trench that I will go myself but my friend, who is lying beside me, prevents me from leaving, saying that he is afraid today that I will not return, just like Gershonas. Nevertheless I crawl from the pit, dragging the walkie-talkie with me and tell my commander that I am going to fix the broken cable. He looked at me as though he understood, and said: go, avenge, but be careful, you are still young and you must live.

I begin to advance on all fours and to get further away from my post. I drag the cable that I want to repair. There is no marked path. I wriggle on my stomach through the mined enemy field, pocked by falling bombs. I wriggle and crawl. Here and there I see the bodies of soldiers, but who knows how they were killed? I continue with difficulty. I have only one thought: how to make it to the spot where the cable was disconnected. I understand the importance of communication between us and the second infantry platoon. I am exhausted. Although it is freezing, I am covered with perspiration. Lo and behold! I have reached the spot where my phone line ends.

I begin to search frantically for the other end of the cable that moved after it was disconnected. After a long search I find it and begin rejoining the ends, but then something terrible happens. Suddenly a bomb explodes next to me. I fall on my face from the blow so that I will not have to see my death open-eyed. I suddenly feel warmth in my hand as though my hand is paralyzed and my fingers are clenched like a fist but I can move them. With my last ounce of strength and one-handed, I join the two ends temporarily and hold tight so that they will not come apart.

With every passing moment, I am getting weaker and weaker. The thoughts that run through my mind at the moment are embarrassing, but I do not let go of the threads of the cable. I hang on to them for dear life. I had only one hope – to get out of this hellish situation in which I find myself.

I suddenly hear the shouts of our army on the offensive; I am overjoyed, the joy of a person in danger who sees help on the way. A group of soldiers approach me and ask what I am doing here. To this day, I have no idea whether it was because of joy or weakness, but I was hardly able to briefly explain why I was lying there. Two soldiers lift me, place me on a field stretcher and carry me to their unit's First Aid hut. As soon as the doctor tore my coat and shirt off me, I noticed the blood spurting under my clothes. Again, I do not remember anything because I passed out and only regained consciousness at the field clinic where everything came back: I remembered what had happened to me and why I was there. They operate on my right hand and move me to a field hospital in Ivanovsk. I spent a year in the hospital and when I was released I was awarded a Red Star medal for that campaign at the front.

I was not the only soldier who fought the Nazi beast wholeheartedly because we, the Jews, also had our own account to settle with Nazi Germany.

Dr. Solomon Atamok, who served in the Lithuanian division reports that the Israeli Association of the Veterans of the 16th Lithuanian Division has a list of 1,250 names of Jewish soldiers who fell in battle. Most of them were young and had just entered adulthood or left young wives and children. There were fathers and sons who perished as well as brothers and relatives.

An incomplete list shows that over 4,500 Jews fought against the Nazis in the Lithuanian division. They were people, who until the outbreak of war, studied (in Yiddish) at Jewish schools, at the ORT college, spoke mama loshen (Mother tongue in Yiddish) and sang Yiddish songs.

The vast majority of the remnant of the Lithuanian division (some wounded and invalid) made it to Israel and integrated with their children and grandchildren. It is no less impressive that the State of Israel adopted the Jewish fighters of this illustrious unit.

The memory of the courage and sacrifice of the soldiers of this unit, along with that of all the other Jewish soldiers who fought the Nazis and their collaborators, will forever remain a part of the history of our nation; even though they served in a foreign army, to a large extent, they fought the war of the Jews. One of the survivors of the Lithuanian division expressed it very succinctly: "In fact it was a red division, but its content was blue and white."

On Wednesday, the 5th of September, 1979 a funeral ceremony was held to bury the ashes of the 16th Lithuanian division at the military section of Har Hazeitim (The Mount of Olives) in Jerusalem.